|

"Oh! Dogma (Up Yours!)":

Surfing the Third Wave |

|||

| Maria-Elena

Buszek |

|||

| As a baby

academe, mid-dissertation, with the dubious

distinction of studying feminist artists'

love of pop divas and porn stars, my research

is forced to address two of the greatest question

marks currently plaguing cultural studies:

postmodernism and third wave feminism. Not

that I'm even pretending to have concocted

any neat definitions, mind you. My studies

actually come from a ridiculously simple place:

by all accounts, I am apparently a third wave

feminist living in the postmodern era, so

why not hash these "-isms" out while the hashing

is good? Now, "postmodernism" is a dilemma

with which most folks have been frustrated,

if not familiar, ever since it was generally

agreed upon that our post-WWII world has proven

itself increasingly unwilling to evolve according

to the ideals of solely a dozen-or-so white,

Western male intellectuals. That said, I suppose

it would work to say that feminism, too, has

proven itself increasingly unwilling to evolve

according the ideals of solely a dozen-or-so

white, Western female intellectuals. As many

of us know, for feminism, this fidgeting has

come in a couple of blurry stages. The popular

women's movement of the sixties and seventies

arguably emerged after Betty Friedan's The

Feminine Mystique introduced many women

to the idea that a revival and re-tuning of

the female abolitionists' and suffragists'

spirit (or "first wave" of the women's movement)

was long overdue. This "second wave" of feminist

activists took it upon themselves to herd

up and scrutinize the many and varied goals

of their hundred odd years' worth of foremothers

in an effort to settle upon a common agenda

for women activists to build upon and work

toward. Great on paper, except of course for

the fact that this agenda tended to spring

from a decidedly white, Protestant, middle-to-upper

class perspective. Reverting, perhaps, to

the style and pluralism of the first wave,

a new generation of feminist thinkers materialized

- from the ranks of both the second wave and

those born in the midst of its formation -

to question the well-intended restraints that

the second wave had placed upon itself.

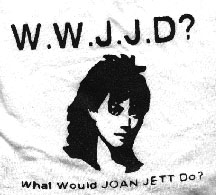

In her 1996 Art Issues essay, "Virtue Be Damned: A Modest Proposal for Feminism," Libby Lumpkin tackles perhaps the most persistent problem of second wave thought: the belief in an inherently virtuous womanhood. (An ideal that, Lumpkin argues, has hindered the feminist movement through both the unrealistically high expectation that it sets for women's behavior and the limits it places on women's ability to learn through misbehavior.) However, the reason that I keep returning to Lumpkin's essay is for its spot-on articulation of the sense of freedom, as opposed to dogmatism, that attracted young women such as herself to the second wave in the seventies: "Back then, feminism was exciting and sexy; it promised the joy of power, the right to be exuberant, naughty and self-indulgent, the right to be not only our best selves, but our worst selves - and in public." In the early seventies Lumpkin and her girlfriends prowled Texas' Interstate 20, defining feminism through naughtiness, not through nurturance. "Fuck virtue - we drank beer and roved in old Cadillacs."[1] Growing up as a punk Hispana in the lower-to-middle class, box-house suburbs of the Midwestern U.S., my own view of feminism's promise wasn't much different in the mid-eighties than it was for Lumpkin and her girlfriends a little over a decade earlier. However, unlike the yin-and-yang identity model of Lady Bird and Lyndon B. Johnson that Texan Lumpkin found during her adolescence, many of us would find our own delicious models of audacity, pleasure and contradiction not in politics but in pop culture. We were also living lives that never really knew a world without feminism - and, frankly, those of us young enough didn't really know what feminism was "supposed" to mean in the first place. I mean, it was out there, alright - on the news, in articulate soundbites and compelling protest imagery. I was intrigued by the panic in my father's voice whenever these "women's libbers" (as he churlishly referred to them) materialized in the headlines. Weren't they saying something about... "empowerment"...and "equality"...and, erm, is it just me or did loud and scary figure in there, too? That already sounded a lot like women whose glamour and outrageousness were providing me with templates sure to freak my dad out...not to mention a tidy little "ism" to throw in with the rest that teenagers like to have handy when they are figuring out who to be. "Where do I sign?!" With absolutely no knowledge of Simone de Beauvoir or Laura Mulvey (much less Andrea Dworkin or Catharine MacKinnon), phallogocentrism or even Ms. Magazine, many of us third wavers just made feminism up as we went along, fashioning ourselves after the models that best resembled our cursory ideas about the women's movement. The moment that perhaps best represents my early feminist awakening happened, as would many, in front of the tube. I was blissfully snacking and watching videos after returning home from school (we didn't have cable, but settled for MTV's 1/2 hour, welfare cousin, MV3, broadcast weekdays on a Detroit UHF station), when up popped an interview segment with the tarty Dale Bozzio and her tacky New Wave band, Missing Persons. Naturally intrigued (Oh, what I at age twelve would have given to trade in my fussy braids and UPS-brown St. Raphael's uniform for Dale's pink-streaked bleach job and cellophane-wrap jumpsuit), I scooted closer to the box. Recorded on an L.A. beach, Dale looked even trashier than usual by the light of day; her trademark fuschia Nike-swoosh blusher and Cleopatra-inspired blue kohl liner over white pancake makeup were rendered positively plastic by the effects of the sunlight. Entranced by the visage of this proudly gilded lily, the spell was sealed when she opened her mouth to answer questions: the warbling-pixie singing normally there was replaced by a deep, no-nonsense speaking voice. Front and center, and without giggle or hiccup, Dale proceeded to speak for the rest of the (otherwise male) band; she was smart and articulate and funny - basically, everything I'd ever been taught bad girls who dressed like that and teased out their hair and were bossy with boys were not. I froze with excitement over the thrill of the contradiction. Maybe it was something in the air. It shouldn't strike anyone familiar with the last 25 years of feminist history as surprising to find that the early eighties marked not only the popularity of glamorous guttersnipes squealing away on top of synthesizer beats, but the point at which constructionist feminism became a force to be reckoned with. By this time, years of attempts on the part of the second wave to define an "essence" of womanhood (hence, a common sisterhood) had in fact only served as divisive. The loudest feminist voices on the scene seemed to be saying that you were either "in" (with your suspicion of sex, disdain for the sight of naked women not falling into a prehistoric goddess-mother type, and regard for protectionist legal activism) or you were "out" (with your dog-eared copies of the lesbian porn mag On Our Backs, closet full of high-heels, and First Amendment defenses). The essence of our common gender and oppression dictated it! (Regardless, it would seem, of one's color, religion, nationality or sexual orientation.) Of course, this did not sway women who, like Lumpkin's Cadillac full of boisterous belles, felt that feminism had promised women the opportunity to not only be both their "best" and "worst" selves, but the right to piece together and dole out those selves any way they damn well pleased: Dogma be damned! Enter the third wave...Enter feminisms. Of course, in my juvenile delinquency, I had absolutely no idea that any of this academic nonsense was going on. However, its presence could arguably be felt not only in the female pop idols I was busy worshiping, but more so in the generation of young feminists of which I was a part. Although by age fifteen I had buried the Missing Persons EP's waaaaaay back in my record stacks ("Tsk...that blippy electronic stuff is, like, so tired"), I had gained plenty of new ammo for my arsenal of personae. Naturally, the popularity of D.C. and California hardcore had sent plenty of us digging through the used record stacks for earlier British punk chestnuts. My girlfriends and I gobbled up everything Siouxsie Sioux touched, and imitated her bottle-black ironed 'do as well as her practiced snarl. When she sang of domestic dysfunction ("Happy House") or of female schizophrenia celebrated ("Christine"), we absorbed her dramatic tales of misery and mystery into our own repertoire of teenage angst. But, for all her wailing hysterics, Siouxsie somehow managed to be terrifyingly gorgeous and self-possessed - Jackie O. meets Medea. Less glamorous, but certainly no less interesting, was X-Ray Spex's Poly Styrene. Teenaged, chubby, and with a mouth full of braces, Poly looked and acted a lot more like we did, but had much keener senses of humor and conscience. She taught us how to use the word "consumption" in the Marxist sense (very useful in my Smiths-inspired "Meat is Murder" phase), and gave purpose to the contradictions I instinctively admired in women like Dale years earlier. Dressed in head-to-toe bondage gear (complete with biker cap), Poly gave a big two-fingers up to society's physiognomic bent in her satirical masterpiece, "Oh! Bondage (Up Yours!)" Many were the nights that my little pack of raccoon-eyed girlfriends and I stumbled out of shows at the Omaha, Nebraska V.F.W. hall, chain-link jewelry rattling and triumphantly bruised, howling its chorus - "Oh bondage, up yours!/Oh bondage, no more!" - as if our mere, S/M inspired presence in the pit had been a blow to the patriarchy. But, just when we may have become unwitting tools of constructionist limitations, goddess bless everyone's favorite punk essentialist Lydia Lunch. Bursting out of black vinyl corsets and stretch-minis (and always, always wearing at least four-inch heels), Lydia was out to steal back the specter of female hysteria and use it to beat the corpse of Freud violently about the head and shoulders. Lydia wrote, sang and shrieked about menstrual blood, Dionysiac orgasms, matriarchal outerspace colonies of the future, and her fascination/repulsion for the sorry ways of men. Pointedly situating herself as woman against the really fucking scary alpha-male, junkie personae of Jim "Foetus" Thirwell, Stiv Bators and, of course, the Nicks (Cave and Zedd), she transformed the dark muse of the nineteenth-century Romantics and Symbolists into dark collaborator. (With top-billing to boot!) Best of all, she always rose from the swampy back alleys of New York or New Orleans like St. Dymphna (her self-described patron, saint of the sexually insane), experienced yet uncorrupted, putting it all down on paper while the boys were on the nod with a needle dangling out of their arms. While Lydia was spending those inevitable menstrual cycles in a blood hut, that other consistent snag in constructionist gender theory - motherhood - started popping up among the ranks of my scary heroines. X's brilliant singer/songwriter Exene Cervenka divorced her musical soul-/band-mate, John Doe, and went on to other (re)productive stuff, working highly politicized paeans to motherhood into the spoken-word performances of her "Rude Hieroglyphics" tour. (Where she shared the bill and the stage with none other than the confirmed anti-mom Lydia Lunch, and the two women warmly feuded over the merits of their respective positions on the subject of childbearing/rearing.) Before Exene, Nina Hagen, that nutty queen of the Continental New Wave scene, had gone the way of the mom, audaciously posing with her first child, Cosma Shiva, as the Virgin and Child on the cover of her Nunsexmonkrock album. My being a big sister who had - in old school Spanish style - been more or less left to the raising of her younger siblings, these funky and righteous maternal models tempered this otherwise strange (among the detached families of white suburbia) element of my heritage. Where Lydia had helped make the love of my uniquely femme self - which I had inherited from my strong and extremely sexy Hispana mom and aunts - an activist statement, punk mamas like Exene and Nina expanded this to my blatant maternal instincts as well. I was picking and choosing from the supposedly binary poles of feminist thought to find something comfortable in the spectra between. All this is not to say that we were too cool for anything but chick esoterica. Although Madonna still seemed too boy-centric for us to even consider as campy, we shared the guilty pleasures of our mutual childhood heroines and suburban environs. Wandering around the abandoned and ever so exotic downtown, we'd run from block to block, posing with our fingers as handguns in each doorway and on each corner while humming the Charlie's Angels theme. We bought fat, metal bracelets in homage to Wonder Woman. And damn it all if we didn't confess (among ourselves, of course) to our love of Pat Benatar. We may have worn our Killing Joke t-shirts while affecting the sullen depth of Nico (at least while in plain sight of anyone we wanted to impress), but at our sleepovers, we memorized the defiance-dance of the prostitutes in Pat's "Love is a Battlefield" video. Talk about the ultimate staging of a bad girl revolution! A brothel full of rattily sexy hookers (led by hessian Pat and her fabulous underbite) turned gang of avenging Amazons! Forming a solid wall of big hair and whore-couture, they beat their primitive war dance right over their pimp, through the streets and, ultimately, into the light of day. And, even after the freedwomen share their sorrowful goodbyes, Pat was still able to walk victorious into the sunrise. Pat may have been a cheesy metalhead, but it was she who managed the Broadway styled video-musical of our dreams. Ah, if only Siouxsie hadn't been too cool to have done it first. So why the surprise when Pat Benatar wound up on the Lilith Fair lineup? Granted, most of us Do-It-Yourself feminists, now in our twenties and thirties, wound up in the same women's studies programs and consciousness-raising groups instigated by our foremothers, where we learned that many of those unpleasant backseat gropefests are known as date rape and Teresa de Lauretis was politicizing women's cinematic vengeance well before Pat's "Battlefield." Nonetheless, our unique incorporation of unwittingly feminist icons into our collective pantheon certainly remains a staple of the emerging third wave of the women's movement. Unfortunately, academia and the art world haven't thought to pay this much notice. While the so-called "Bad Girls" of the YBA (Young British Artists) and SoHo art scenes are sending London and New York critics into seizures - crying "Pandering to the patriarchy!" as if feminists who created work about sex and hedonism were something new, much less inherently misogynist - third wave 'zines like Bust are publishing their works as icons of the continued resistance. One only has to go to the cathartic musical vomiting of Courtney Love and Diamanda Galas to get a sense of where Tracey Emin's purges in paint, sculpture, and video come from; or to Lydia Lunch's morphing photo self-portraiture (hair strands become octopus tentacles, torso becomes a male hand) and pornographic, quasi-autobiographical films to understand the disturbingly fascinating painted nudes of Lisa Yuskavage and intricate group/sex photography of Sam Taylor-Wood. These are women whose femaleness was informed by rock, by punk, by a DIY ethos in which anything went as long as you came out with what you felt was some real grasp on yourself and your power when you emerged. These women don't fit into a traditional feminist "party line" because they were only informed of this mythical animal upon being inexplicably told that they were not feminist, even anti-feminist, because their work does not resemble that of Judy Chicago or Audrey Flack. To most third wavers, this is like saying The Pixies aren't rock and roll because they don't sound like The Who, or Lauryn Hill isn't R&B because she doesn't sound like Etta James. Art moves on, and movements evolve to consume and combine with its offspring. The feminist movement is no different, and its various generations need to let go of the primacy it places on its own agendas and its own innovations to realize that these are not only the same things that drew new generations to their movement in the first place, but the same issues that created the little monsters that question them. We are the children they raised - but we're also products of the (high, middlin' and just plain junk) culture of the '70s and '80s. The pluralistic ideals of the era's constructionist feminism gave many of us a language through which we might put our guilty pleasures into perspective; defend the transformative appeal of heroines beyond The Earth Goddess; and even wade into the useful pool of essentialist thought without fear of being drowned there. Most importantly, constructionist models allowed us to keep our DIY sensibility intact, shunning orthodoxy and embracing transgression in its myriad forms. Our familiarity with surfing the New Wave amounted to a third wave comfortable with redefining feminism so that it included us, and as such it ceased to be a dirty word for a new generation of young women. While some have criticized the lack of cohesion (ie. "sisterhood") in third wave culture - pointing to the brevity of organizational attempts such as Riot Grrrl as third wave failures - perhaps it is precisely this element that sustains us. The multi-generational and -dimensional feminist outrage that followed Time magazine's 1998 declaration of feminism's demise-by-diaspora - with its ridiculous cover that placed Ally McBeal as third wave representative in the feminist continuum - bears this out.[2] Ally alongside Susan B. Anthony and Gloria Steinem? Mmmmm...try Joan Jett and you're getting a little warmer.

Notes 1 Libby Lumpkin,

"Virtue Be Damned," Art Issues 42

(March/April 1996): 18-19.

back |