|

Creating Feminist Solidarity: Moving from

Isolation to Communication

|

||

|

Morgan Gresham

|

||

| In her roundtable response, Cambria draws on Donna Haraway’s definition of solidarity that counters claims of relativism by pointing to local, critical knowledges: “alternative to relativism is partial, locatable, critical knowledges sustaining the possibility of webs of connections called solidarity in politics and shared conversations in epistemology” (584). Recently, I have been studying the rhetorical nature of disclaimer messages that appear on pro-anorexia webpages. These disclaimers, I posit, are part identification and part manifesto in which many of the young women who write or claim them identify as feminist. Given that, the spaces that these disclaimers invoke are, if nothing else, webs of connection that connect politics and epistemology. These ‘webs of connection’ are particularly interesting here as we consider what it means to have a feminist identity. While I do not focus on the rhetorical study of pro-ana sites here, the theoretical underpinnings on identity, appetite, and feminist process influence other conversations centered on what it means to be a feminist, to be in feminist process, and to create feminist solidarity. Here I will draw from the work of author Caroline Knapp and song-writer Ani DiFranco to weave strands of feminist process together. Who are the feminists? In the 2008 feminist workshop at the Conference on College Composition and Communication, a significant part of our day was spent wrestling the term “feminist”—defining, historicizing, disputing, and claiming. We discussed global feminism and visible feminism. As Hildy Miller suggested in her talk at the workshop, because our tendencies to create straw women and beat up our feminist mothers limits what counts as feminism, we talked at length about the waves of feminism—first wave, second wave, third wave, fourth wave—and critiqued the metaphor of waves, discussing the ways in which wave terminology was bothinclusive and exclusive. In her text on Appetites, Caroline Knapp writes about the roles which feminists and feminism have played in helping identify hunger and appetite:

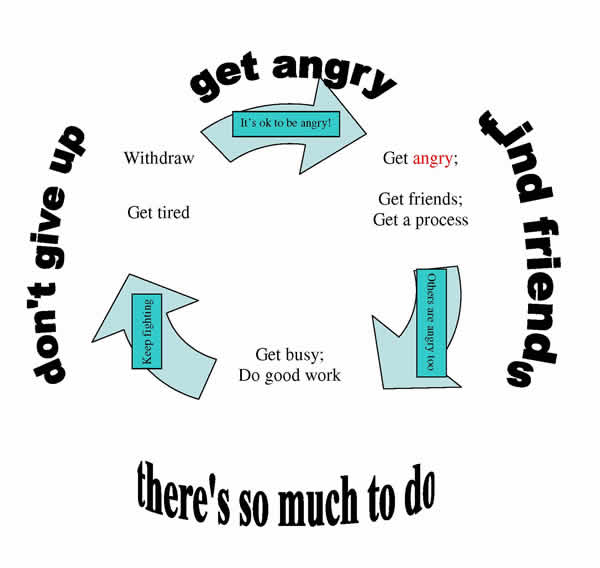

In my women’s studies classes in the late 1980s, we laid claim to the power of language—renaming mostly—and created a Women’s Collective, a space where young feminists could come together to talk about feminism, to claim the power of language, and to connect to one another by sharing our stories. Looking back on those women’s collective meetings, I see that we were a particular kind of feminist—a kind of feminist that is now being described very differently by writer Meg Wolitzer. Wolitzer, the author of The Ten-Year Nap, was recently quoted in an ABCNews article suggesting that feminism is changing to accommodate younger women who perceive “having it all” as an impossibility, and are opting-out of paid employment to rear children, when possible. She writes, “There is this generation of younger women who don't feel they need to adopt the kind of frizzy-headed, clog wearing feminism of their mothers and grandmothers [...] the old models do fall away but a lot of the good stuff has been left behind” (Goldsmith). What’s interesting here is the definitions of feminism being juxtaposed—if we consider on one hand the “frizzy-headed, clog wearing feminism of their mothers and grandmothers,” what is the flip side of that? High-heels and perfectly coiffed hair? Is this the coming of age of ‘girl power’? Knapp describes the tensions between feminist waves that were embedded clearly enough in an Enjoli perfume commercial: with it, she suggests, the “[c]ase closed, end of struggle, a woman’s triumvirate longing—for ambition, family connection, and sexual expression—available not through the grueling work of social change but through perfume, smart suits, leather accessories” (Knapp 147). As a woman who came of age in the 1980s, it is no wonder then that this description lays bare my own struggles with feminism. In the workshop, we asked the questions—who are we and what are we trying to do? When do I identify as feminist? Although I have been a strong advocate for feminist pedagogy and feminist administrative practices, it is occasionally difficult to do so in light of student evaluations that degrade feminist practices or in professional development discussions where I am expected to ‘take charge and tell us what to do.’ As our discussion at the workshop evolved and we talked about stealth feminists and young feminists, I/we realized a shift from identity and identification to outcomes, with a focus on action and doing. What do feminists do? In my ‘old age’ I have discovered that I am angry most of the time. I am angry that people don’t understand what I do, that people don’t care, that it is harder and harder to get people—anyone, but young women especially—to identify as feminists. As I’ve said before, I think if I hear “I’m not a feminist, but” one more time, I may just start screaming until the happy little men with the funny white jackets come to take me away for good.... But, as I say that, I realize that it’s blatantly untrue. I am learning to work within the system to make change, and I am learning that, if feminism has a process, it’s this: We get angry, Get Angry

As feminists, there is much that we find we should be angry about—sexism, racism, ageism, heterosexism, the status quo. But much of the time, the angry moments that we have are isolated. Something disrupts our own sense of self or security, and we get angry. Knapp declares that “pain festers in isolation, it thrives in secrecy” and words, she says, “are its nemesis” and “a prerequisite for moving beyond it” (158). Getting angry gives voice to the pain that we encounter on a daily basis. In turn, speaking that anger opens the space to response, and to conversation. Those conversations are connections, which as Knapp points out, are freeing: “the public battlefields may be private ones today, but the dynamics are largely the same. Anything that connects you—to the body, to the self, to other women—can free” (161). Get Friends

bell hooks says that “Choosing love, we also choose to live in community, and that means that we do not have to change by ourselves.” Change is difficult, especially when we are working to change not only ourselves but the world(s) around us. We still need “safe spaces”—places to identity ourselves as “femin”ists and other –ists because

Feminist spaces, however, do not have be women’s spaces, although there is certainly a need for women’s spaces as well; rather, as we are constantly reminded, words matter, and we need to be able to claim our identities and connect. Get a Process Interestingly, as academics, getting a process is easy, especially in the realm of feminist pedagogy and feminist activism in the classroom where a number of different resources exist. Although it is important to acknowledge and lay claim to names that sustain us, with process, it is so much in the doing. Get Busy

Doing good work feels good—an ethic instilled in part by second wave feminism.

A transition happens in this phase, as we move from seeing results to not seeing enough results or not seeing results fast enough. For me, this is the make or break stage in terms of feminist solidarity. If, in this phase, there exists a group of like-minded individuals working together toward a common goal, offering one another support, change continues, progress continues. If, however, everyone gets “busy” and those connections are lost, we get tired. Get Tired

“If only women felt less isolated in their frustration and fatigue, less torn between competing hungers, less compelled to keep nine balls in the air at once, and less prone to blame themselves when those balls come crashing to the floor” (Knapp 154). Knapp captures here the intense struggles with isolation and despair pushed even further, in some ways, by the multiple feminisms. I want to be a feminist, and I struggle with who that feminist is. As academic women we often struggle with the question of motherhood, and where it fits into an academic career—somewhere in amidst the pre-tenure, post-tenure, and graduate school stages. Navigating the choices we have requires a kind of feminist solidarity, and that is not often found in the popular culture representations of motherhood. Jessica’s description of the worries that surround mothering and motherhood helps me think about it in terms of the work I do, and a constant awareness that I am doing so many things and an expectation that they are all being done poorly (or at least without the attention they deserve.) “Asked if any of this makes her angry, she smiled a little wistfully and said, “I don’t really have the energy to get angry. I mean, what good would it do?” (Knapp 152) Withdraw

So much truth and anguish packed into one little sentence. However, where some women are choosing what Wolitzer calls "the ten-year nap," the women in my experiences—academics for the most part—are prone more to the 15-second nap. Choosing instead to withdraw from the action for a semester or year, not giving up the job completely, but often saying no to the extra work being heaped upon by the academy: no, I will not direct your writing program pre-tenure; no, I will not put in my fifth grant application this week; no, I will not participate in these power-plays. But power remains at the heart of it all. And, for my own part, the modicum of power that these roles offer is what keeps me from ever withdrawing too completely. However, to be able to move out of withdrawal into anger I need to have a support group—a group of feminist mentors—who are basically on call 24/7, thanks in large part to text messaging and email. Whether through email, frantic text message, or a desperate emoticon, we are the forces that keep each other going when feminist activism is difficult. Get Angry Again

But fortunately or unfortunately, I find that after a period of withdrawal, I can get angry again. In fact, I am often angry. But that’s a good thing, right?

Works Cited DiFranco, Ani. (1993). My I.Q. On Puddle Dive. Righteous Babe Records. ------ (1995). Not a Pretty Girl. On Not a Pretty Girl. Righteous Babe Records. ------ (1998). Pixie. On Little Plastic Castle. Righteous Babe Records. ------. (2003). Serpentine. On Evolve. Righteous Babe Records. ------ (1998). Swan Dive. On Little Plastic Castle. Righteous Babe Records. ------. (1992). The Waiting Song. On Imperfectly. Righteous Babe Records. ------. (1996). Outta Me, Onto You. On Dilate. Righteous Babe Records. Goldsmith, Belinda. “Women Are Told They Can Have It all But Is It Realistic?” ABC News Online [http://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory?id=4739284]. 28 April 2008. Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14/3 (Autumn 1988): 575-599. Hooks, bell. “Love as the Practice of Freedom.” Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. New York: Routledge, 1994. hooks, bell. “Building a Teaching Community.” Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994. Knapp, Caroline. Appetites: Why Women Want. New York: Counterpoint, 2003. Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of Anger: Women Respond to Racism.” Sister/Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press, 1984. Miller, Hildy. “Reinvigorating Feminism by Reclaiming Past Feminist Paradigms” Paper presented at Conference on College Composition and Communication. New Orleans. 2 April 2008. Stamper, Cambria. “Women, War, and Solidarity on the Web: Grassroots Tools Counter Lugones’ Narrow Identity.” Roundtable Response. |