|

The Role of Self in Group

Treatment for Women with Eating Disorders |

||

| Shelly

Russell |

||

|

It is estimated that ninety percent of people with eating disorders are female (Rolls, Fedoroff & Guthrie, 1991). Many reports indicate that the incidence of eating disorders and maladaptive eating attitudes may be increasing (Cantrell & Ellis, 1991; Dorian & Garfinkel, 1999; Wakeling, 1996). Some authors estimate that up to 20% of women are at "high risk" due to subclinical symptoms such as an overemphasis on or preoccupation with thinness (Cantrell & Ellis, 1991). Although rates for anorexia and bulimia are not precise due to the secretive nature of these disorders, the incidence rate for anorexia is commonly cited as 1% of the female population and the incidence rate for bulimia varies from 3% to 18% (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Klemchuk, Hutchinson & Frank, 1990). The combined prevalence of anorexia and bulimia has recently been estimated as high as 20% for school age children (Phelps & Wilczenski, 1993). Eating disorders are characterized by severe disturbances in eating behavior (Epstein, 1990). Depending on the model to which one adheres, many other characteristics of people with eating disorders can be identified. As early as 1873, anorexia was considered a psychiatric syndrome and traditionally labeled intrapsychic in nature (Epstein, 1990). The medical model uses specific diagnostic criteria to define anorexia and bulimia (APA, 1994). Recently, a sociocultural model has emerged to include society and culture in the overall conceptualization of eating disorders. A feminist framework places women in society on an "eating behaviors continuum" where body preoccupation exists on the less extreme end and anorexia and bulimia toward the more extreme (Brown & Jasper, 1993). Finally, the introduction of a relational model of self-development (Surrey, 1991b) adds much needed information about female development to the conceptualization of eating disorders. It is proposed that the cultural value of autonomy outside of relationships makes it difficult for women to integrate their interest in relationships with their sense of self (Friedman, 1996). Surrey (1991a) suggests that the larger context of the devaluing of relationships is strongly related to the disturbances women face in relation to food, eating, and the body. The devaluing of connectedness in our culture and the denial of the strength it takes to care for ourselves and others, alienates women's need for a relational sense of self (Steiner-Adair, 1986). There are as many treatment modalities in the literature as there are models of conceptualization. Recent trends that consider sociocultural and historical contexts in models of eating disorders are reflected in the development of treatment protocols. There seems to be parallel movement from impersonal and authoritarian modes of treatment to more empowering, woman-centered treatments that consider the larger social context. This evolution had lead to group therapy being a viable treatment alternative for women with eating disorders (Kuba & Hanchey, 1991; Riess & Rutan, 1992). This study explores the multidimensional nature of eating disorders by examining the process of healing for women in group therapy. Past research with eating disorders has focused mostly on standardized test scores to determine the usefulness of treatment. This approach ignores the interaction involved in group counseling and the potential to uncover important themes related to recovery and treatment. The primary goal of this study is to examine the group interaction in order to illuminate important themes related to treatment and recovery of women with eating disorders. Notions of self are complex and participants discussed multiple 'selves'. It is hoped that these discussions can offer insight into the construction of self. The Social Construction of Eating Disorders It is imperative to build upon our current approaches to eating disorders by understanding and validating the experiences of women in our society. Research that is grounded in the experience of women with eating disorders not only adds to our knowledge but also potentially leads to better treatments. Feminist conceptualizations of eating disorders provide alternatives to other models, which dichotomize "normal" and "abnormal" and offer instead, a view of eating disorders placed on a continuum (Brown & Jasper, 1993). It is proposed that dieting and weight control have become the norm for women, an accepted way of life. The similarities between people who struggle with anorexia and bulimia and those who struggle with dieting and exercise allows us to question the traditional understanding of eating disorders. It seems illogical to pathologize and stigmatize individuals at the extreme end of the continuum (people with anorexia and/or bulimia) at the same time as behaviors on the lower end of the continuum (dieting and exercise for weight control) are rewarded and praised (Brown & Jasper, 1993). The societal value of thinness and the Western tendency to base much of a woman's value on appearance all bear tremendous significance for women's relationships with their bodies. The internalization of social standards impacts women's psychological development leaves them vulnerable to negative body image. A female's relationship to her body is distorted by the fact that society teaches girls that their physical appearance is of the utmost importance. Essentially, girls are taught to be attractive, not active, and thus parts of a whole self are fragmented and excluded from their identity (Young, 1990). Culture gives girls and women ambivalent messages about the female body: namely that personal worth is measured exclusively by the appearance of the body, and that the female body is shameful. As Nancy Chodorow (1989) states, "the flight from womanhood is not a flight from uncertainty about feminine identity but from knowledge about it" (p. 43). A woman learns from the culture that her body is her life's work. Eating disorders seem to be connected to the level of comfort or discomfort people have with their bodies (Young, 1992). Cross (1993) notes that women are paradoxically both alienated from and attuned to their bodies at the same time. The evaluation of self for eating disordered individuals may be largely or solely based upon their perception of their bodies (Hesse-Biber, 1996; Pipher, 1995). At the same time, individuals with eating disorders are never satisfied with their bodies and usually are out of touch with physical sensations such as hunger (Epstein, 1990). The female body is an available arena for the expression of the confusion of female identity - and the "self as body" may be the only conceptualization available to women with eating disorders (Mahoney, 1990). Conceptualizing eating disorders as a manifestation

of the social views of self, takes away the

guilt and shame of a disorder that been attributed

to an attempt to reach an unobtainable beauty

ideal. Research suggests that eating problems

start as strategies to solving problems (Thompson,

1992). The idea of eating disorders as coping

mechanisms (Brown & Jasper, 1993) is a

feminist idea that does not discount the societal

pressures or the discrepancy between the reality

of women's lives and current representations

of them. Eating disorders are about more than

food and appearance; they can be conceptualized

as a search for self. This study sought to

understand the meaning of eating disorders

for women and the process of their recovery. Methodology Participants Participants were voluntary adult members of an eating disorder psychotherapy group (6), members of the reflection team (3), and co-facilitators (2). Client participants were women who expressed interest in joining a 2-hour per week, 14-week group for eating disorders. Participants indicated some evidence of purging and restricting behaviors, however, there was no formal screening process and clients did not have to fit DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. The client participants ranged in age from 18 to 37, incomes indicated middle class socioeconomic status, and all participants were White women. The duration of the eating disorder was not available at intake but client participants were assessed as ready for group treatment by a primary therapist. The attrition rate was expected (McKisack & Waller, 1996) but notable. Session one began with 9 participants. After sessions one, four, and seven, one member dropped out of the psychotherapy group. Other participants included members of the reflecting team. The team was composed of a staff member from the agency, a volunteer therapist, and a community member. The process of reflecting includes watching the group behind a one-way mirror and then reflecting to the group and therapist(s) what they have observed (Anderson, 1987). Research suggests that reflecting teams can be useful for their contribution of multiple perspectives and demonstration of changing ideas through discussion and negotiation (Biever & Gardner, 1995). The use of reflecting teams is based on the premise that the group or system is stuck in sameness and the reflecting team offers different points of view that group members might take into consideration (Anderson, 1987). Team members bring their own perspective; just as each group member may be in a different place of recovery. Qualitative studies have substantiated the helpfulness to clients of the reflecting team's multiple perspectives (Smith, Winton, & Yoshioka, 1992; Smith, Yoshioka, & Winton, 1993). Reflecting teams are useful in demonstrating how ideas change through discussion and negotiation. Further, they propose that the client knows what is most useful for them (Biever & Gardner, 1995). A context is created through the process of reflection where the concept of expert is de-emphasized and the possibilities and boundaries are expanded for both clients and the therapist (Gorman, Lockerman, & Giffels, 1995). Some might argue that reflecting teams are inherently problematic due to the potential for imposing 'expert' advice. However, recent authors (Russell & Arthur, 2000) have illustrated the use of reflecting teams in a way that is respectful to women. Specifically for women with eating disorders, who often have a negative view of themselves and difficulty looking in the mirror, the one-way mirror offers a different interpretation through the diverse perspectives gained from the reflecting team's observations and reflections. The group can take what they want from the reflecting team discussion and leave the rest. Data Collection and Analysis Over 28 hours of group therapy were transcribed and analyzed. Grounded theory supported by feminist principles was the method of data analysis used in this study. Grounded theory was chosen for this study because literature on eating disorders has been informed by mostly quantitative methodological approaches. The major emphasis in grounded theory that separates this methodology from others is the emphasis on theory development (Strauss & Corbin, 1994). Theory is generated in the course of research through close, systematic inspection of the data (Henwood & Pidgeon, 1992). Further, grounded theory is more than a description of data; it is an interpretation that is constructed and informed by the data collected (Strauss & Corbin, 1994). The purpose of the interpretation is to represent and make meaning of human experience and behavior. Specifically, procedures outlined in Strauss and Corbin (1990) were followed for data analysis. Grounded theory and feminism share some common principles. The notion that reality is socially constructed is an underlying principle of both grounded theory and feminism (Wuest, 1995). A feminist perspective is a lens that adequately allows this group experience to be both unique and common in some way to all women (Brown & Jasper, 1993). Likewise, grounded theorists are motivated by the knowledge that all concepts and ideas about any particular phenomenon have not been fully explored (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The proponents of grounded theory suggest that because the theory is developed so closely to the data that it is likely to be useful to those who participated in the study (Turner, 1981). One of the most important feminist research principles is that the "knowledge produced by the research should be useful for the participants" (Wuest, 1995, p. 129). The theory that is uncovered must be placed within a context where 90% of women are dissatisfied with their bodies and dieting is the norm (Brown & Jasper, 1993). Corbin and Strauss (1990) suggest that broader social and structural conditions must be analyzed and integrated into the theory. The focus on contextual influences is consistent with both feminist thought and grounded theory methodology (Wuest, 1995). One of the premises of grounded theory is that the theoretical assumptions of the researcher are suspended and themes emerge directly from the data. Although in theory this seems like a reasonable assumption, in reality this kind of objectivity is difficult to achieve. Every effort was made to allow themes to emerge directly from the experiences of the women in the group and no assumptions about women with eating disorders' identity development were forefront at the start of this research. Results The Grounded Theory

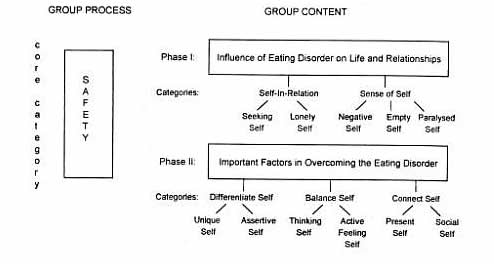

The Centrality of Safety In grounded theory, the core category is the central phenomenon or the basic social process being studied. The central phenomenon became clear through asking questions about the connections between the themes that emerged from analyzing participants' experiences. It became apparent that the movement of the therapy group from one phase to another was dependent on the level of safety experienced by group members. Safety, a basic sense of trust and security or being safe from danger or damage, was the overarching framework within which the therapy group functioned. When safety was low, the group tended to discuss the eating disorder and its influence. When safety was high, the group discussed strategies about how to overcome the influence of the eating disorder. When safety issues were paramount in Phase I, a lot of discussion about safety and long silences ensued in the group. For example, one participant expressed her need for safety in the group, "…[O]ne of the reasons why I'm scared to say anything is the fact that I need to express it in a place where I feel - where my expression is secure." The group returned to a discussion about safety a number of times before their interactions and content moved to a deeper level of engagement. Thus, the safety of the group was discussed throughout Phase I but not practiced consistently until Phase II. As the safety of the group began to increase, the majority of discussion shifted to focus on strategies to overcome the eating disorder. For example, a group member commented about feeling safe in the group, "I don't know if it's because we're all feeling more comfortable that we're sharing more, that we're - I feel like we're getting somewhere." In short, Phase I focused on the eating disorder and Phase II focused on overcoming the eating disorder. Overall, the quality of Phase II is more active, unlike Phase I, which focused on talking about issues instead of implementing strategies. Phase I: Influences of Eating Disorder On Life and Relationships During Phase I, the safety level was related to discussion about the eating disorder and its effects on the lives of the individuals and the interaction of the psychotherapy group. Two major categories emerged from this interaction: self-in-relation and sense of self. . Much of the discussion about the eating disorder and its influence centered on the relationships or lack of relationships developed by this group of women. Two minor sub-themes emerged from the self-in-relation theme. The seeking self emerged as the person who never seemed to be satisfied with who she is in the moment. The seeking self was illustrated by a number of participants, "…I always kind of put on a front and everyone thinks I'm that way but then when I get home and I'm alone - I know that I am the total opposite... But I like everyone to think I'm that way." It seems participants felt they had to put on appearances and be something or someone other than herself in order to carry on relationships with other people. Another example of the seeking self had a comparative component, "But still I feel I'm not qualified to be a part of this world, if this makes any sense, cause I don't feel that I - I live up to what is considered ideal, beautiful." The overall quality of the seeking self seemed to be an inability to be in and enjoy the here and now because of looking to make someone or something better in order to take the focus off self. The second sub-theme that emerged from self-in-relation is the lonely self . One participant's voice can be heard through the following example, "I think it has to do with the isolation thing. Like, you know, we go through our days, and probably all of us keep the secret to ourselves for the most part. The eating disorder isolates you and it keeps you quiet it's isolating you again from getting close to people." Physical and emotional isolation prevents any meaningful connections with other people and it seems that eventually the only constant is the eating disorder. Further, participants shared their difficulty with relationships, "I just realized that this man that has become a very important part of my life, I haven't even told him that I have an eating disorder. I'm not sure why that is." The lonely self speaks loudly to the lack of support and essential connections in the group members' lives. There seems to be an overall quality of being unable to make meaningful connections with people resulting in a lonely and often alone self. . The other major theme that resulted from the interactions around the influence of the eating disorder on lives and relationships was sense of self. Generally speaking, the sense of self can be described as how each woman in the group felt about her personal being. This theme differs from self-in-relation in that the qualities are more internalized. Three minor sub-themes were uncovered and included the negative self, the empty self, and the paralyzed self. Group members often talked about two separate voices in their head and the negative voice (the eating disorder) seemed to be both persistent and convincing, "…[M]y head started playing games on me. It said - made the worst-case scenario out of every single thing in my life all of a sudden. I mean a problem for me is like the world is ending. The smallest little thing can be like catastrophic." The negative self seems to be characterized by an overall quality of disallowing or rejecting any positive attributes of self, be it a thought, feeling, action, or characteristic. The empty self was described as a feeling of having nothing left. This theme is illustrated by a participant, "You know one day I might want to be really athletic and be able to be like the most fit woman that there is and the next day I just - I want to be the skinniest person that there is." Thus, it seems that if there is anything in the self it is something about the eating disorder. The empty self seems to be an overall sense of hollowness or a void within the individual. Most time and energy seems to be taken up giving life to the eating disorder and anything unfamiliar, like emotions, seems unmanageable. An empty echoing ache resounds and the empty self sees herself as nothing. The third sub-theme of the sense of self, the paralyzed self, left the women in the group immobile. One participant expressed this immobilization, "And when I carry it (eating disorder) around myself it's almost like it's overwhelming… I just think it's so huge it paralyzes me." At some points in the psychotherapy group, the group itself also seemed paralyzed. A sense of selflessness or lack of self makes decision making virtually impossible. "I can stand in front of the closet for like an hour and I can never find the right outfit, it's not good enough…it's gotta be perfect." The paralyzed self seems to render the women in the group frozen and defenseless. Phase II: Important Factors in Overcoming the Eating Disorder Three major themes, namely, the differentiated self, the balanced self, and the connected self, as well as six sub-themes emerged from the data through discussion about how to overcome the influence of the eating disorder. Although many of these strategies were practiced by the women when outside of the group, a parallel process occurred whereby many of these strategies were practiced and experienced in the group. . The focus of Phase II was on action strategies to overcome the eating disorder. Seeing the self as a separate individual seemed an important strategy in many contexts. Two minor sub-themes of the differentiated self emerged, the unique self and the assertive self. According to accounts by the women in the group, the unique self is also able to separate herself from the eating disorder, "But if I can separate myself from it you know, like that's the eating disorder talking, it wants to bring me to my knees. And that's what it needs to tell me to get power and strength over me, but I'm not like that, I don't need to be like that, that's not who I am. It is like separating myself from it because then I stand a chance." The ability to see the eating disorder as a separate and distinct entity seemed fundamental as fighting to overcome the eating disorder is no longer then fighting against the self. In other words, the unique self can differentiate herself from others and her eating disorder and feel okay about her uniqueness. The second sub-theme of the differentiated self is the assertive self. The assertive self is able to identify opinions and needs and state them to others: "I've been exercising more boundaries around my time…I've been over-accommodating everybody but me, so…" Instead of letting an opportunity to commend herself pass by, the assertive self acknowledges personal accomplishments and accepts praise from others. "…[B]ut I was able to stop and say, you know, and no, I do deserve to do something nice and this just, and it's OK for me to accept generous offers from other people." Overall, then, the assertive self is able to stand up for her beliefs and opinions and take credit when it is due. . The second important factor and major theme in overcoming an eating disorder is the balanced self. This theme seems to be in the middle on a continuum between the differentiated self discussed above, and the connected self, to be discussed below. One participant expressed her balanced self, "If I allow myself to be with good people and enjoy good relationships, have fun in social situations, play and laugh and cry…If I'm willing to grow and change, if I'm willing to try something different…But to see myself be the best I can be, don't do any more, don't do any less." The balanced self consists of two sub-themes, the thinking self and the active feeling self. The thinking self became apparent in the group interaction as they brainstormed around the negative thought, "I'm so fat." One participant challenged this, "What about 'I feel fat' because like, I can feel angry or I can feel sad or I can feel resentment but that doesn't sort of mean that's who I am and then I have half a chance of moving to through and at some point it might end…you know if 'I am fat' then it will take 6 months to get unfat, but if I just feel fat today, then there's certain things I can do to take that feeling away or maybe that feeling will pass." Generating alternatives was a strategy that was useful for a number of different issues and brainstorming as a group provided a means for the group to recognize options other than the black or white alternatives. The thinking self centers around thought processes and practicing tactics to combat negative or extreme thinking. The second sub-theme of the balanced self is the active feeling self. The active feeling self finds a place where she can be honest with herself and others about her life and take responsibility and action for her own care, "Commit to reality and be in it. You know life's in progress get in it… I think for me it took a lot of growing up - being willing to grow up." The active feeling self is an engineer of life and feelings and takes an active role in the fight against the eating disorder. In psychological process, feeling and thinking are critically interrelated. This interrelatedness is illustrated through the balanced self where the thinking self and the active feeling self merge. . The third major theme in overcoming the eating disorder is the connected self. One participant expresses the importance of connection in her recovery, "Well, I think for me, one of the strongest parts of this disease is the isolation. When I get into it or get around food, then I stop relating to people and I stop reaching out and I stop sharing and then I start carrying everything…And getting outside myself seems to put it into perspective." Two sub-themes emerged in relation to the connected self: the present self and the social self. The present self can accept support from others. For example, "…[T]hem coming and just accepting me for who I was and saying it doesn't matter what happened to you in the last couple of years, we still love you, we still enjoy having you around…I really didn't think anybody needed me anymore…I must be worth something." The present self is able to be attentive and appreciate the moment in the here and now. For example, one participant confronted a facilitator in session 7 about moving on too quickly, "I just feel I need to say something…And I feel a little bit like jumping away from this topic and moving on, we're not honoring it and it's just like okay, that's a great idea but we'll talk about it next week." There is the ability to be in the here and now whether that means accepting support or protecting self. The second sub-theme that emerged from the connected self is the social self. This strategy made a difference to the members in the psychotherapy group:"It's like being here you can kind of relate, you know, in one way or another." "I think it's made some changes because you're meeting people with the same sorts of problems as yourself and you're talking about it and that is change right there." The knowledge that 'you are not alone' seemed to be both comforting and empowering. It seems that practicing self-in-relation is an important strategy of the social self. The social self utilizes caring people in her life to help combat the eating disorder. Summary These themes from the perspective of the women in the group were uncovered to elucidate what they see as important to recovery. Underpinning the process of recovery was safety as it directed the movement of the group between the two phases: the influence of the eating disorder on life and relationships, and important factors in overcoming an eating disorder. Eating disorders seem to be a dance around and about relationships; including relationships with self, with the body and with the eating disorder. These reciprocal influences are illustrated by the two phases of this group process. Relationships and connection (or lack thereof) can influence the development of an eating disorder and an eating disorder can influence the ability of women to attain and sustain connection. Discussion Previous research on the eating disorders provides support for the two phases reported in this study. Brotman, Alonso, and Herzog (1985) noted that as group treatment progressed, the focus shifted from eating behaviors to more interpersonal relationships. A similar conclusion was reached by Reed and Sech (1985) in their experience working with groups of clients with eating disorders. "In our group we came to believe that the real fear had nothing to do with fat, thin, or food. It was a fear of intimacy…" (p. 20). Likewise, Gendron, Lemberg, Allender and Bohanske (1992) described a process where members of the group reframed their eating disorder from a food problem into an interpersonal problem, thereby suggesting the importance of interpersonal solutions. Group treatment is advantageous because of the dynamics that can develop from on-going interaction as the focus changes to developing a sense of self in relation to others. Self-In-Relation and Sense of Self Increased separation and self-development characterize many early models of development and neglect the notion that others may play a role in the formation of a sense of self (Surrey, 1991a). Surrey's (1991b) self-in-relation model proposes that an autonomous self can be developed within a healthy relationship and that this process is more characteristic of female development. Findings of the present study indicate the importance for women with eating disorders to develop a self-in-relation but emphasize equally the importance of a sense of self. The possibility that a large portion of women's sense of self may revolve around the inclusion of others is not being disputed, as long as it is not to the exclusion of self-experience. Ideally, the two categories work together as Kaplan (1982) describes: the self is enhanced through relationships with others. Literature on eating disorders also suggests that the two concepts of self-in-relation and sense of self intertwine. Hall (1985) describes clients with eating disorders as limited in their ability to form and benefit from meaningful relationships and relates this difficulty to poor self-esteem. King (1994) describes the experiences of women with eating disorders as an exaggerated picture of a common dilemma. These women try to balance: a) the values of achievement with a self-concept defined in terms of traditional females values (like physical appearance) and b) a sense of self that integrates self-identity with relationships to others. Other authors have found that both the sense of self and self-in-relation play a role with women with eating disorders. For example, Roth and Ross (1988) focus on both the interpersonal and self-referential beliefs of the members in their study of long-term group therapy for eating disorders. Steiner-Adair (1986) conceptualizes eating disorders within a larger context by looking at the larger message women with eating disorders are sending. The emaciated female becomes a symbol of a society that does not value the relationships that are essential to female development. The message speaks loudly about a culture that values independence over inter-relatedness. It seems then that self-in-relation and sense of self are integrally connected and may be fundamental constructs in the treatment of eating disorders. If the body is viewed as a metaphor for the drawing of self-boundaries, or essentially as an indication of the emerging self, then care must be taken in the treatment of individuals with eating disorders. The self may be lost in the connection the woman has made with the eating disorder because the eating disorder provides an identity, and perhaps the only sense of self (de Groot, 1994). The emergence of the "real self" needs to take place in the context of a safe, healthy and connected therapeutic relationship (Romney, 1995). "To be well bounded is to know the difference between inside and out, be it food, people, ideas, or values around slimness" (Romney, 1995, p.59). Further, for the individual struggling with the eating disorder, the problem needs to be externalized and differentiated from the self. Differentiated and Connected: The Balanced Self Similar literature can be used to support the three major themes uncovered in Phase II of the psychotherapy group. Romney (1995) describes anorexia and bulimia as "manifestations of both the striving for individuality and longing for connection" (p.53). Romney claims that her recognition of these two compatible needs has informed her counseling practice. "It is up to each person to find the healthy balance that works for her, and treatment should support that search" (p.56). This quote emphasizes the importance of women deciding what represents balance in their lives. Therapists need to be careful not to impose their own definitions of balance. At the same time, alternate conceptualizations of what balance might look like need to be considered given the societal pressures to restrict women's lives. There is anecdotal evidence for the importance of both autonomy (Frederick & Grow, 1996) and connection (Laube, 1990) in the etiology and treatment of eating disorders. Laube (1990) suggests that because the group is a living social system, it provides a parallel process for the being of each participant in the group. In other words, as a member develops connections in the group dynamics, her differentiated self is also developing. Kaplan (1982) also suggests that a balance is achieved between connection and differentiation in women's optimal development: "Connection with others, then, is a key component of action and growth, not a detraction from or a means to one's self-enhancement…" (p.208). The feminist model takes the self-in-relation theory one step further and suggests that society's lack of valuing of relationships and connectedness is a barrier for women to develop a healthy sense of self in relation (Kaplan, 1982; Lazerson, 1992). Results from this study also suggest that overcoming societal messages is an important part of addressing an eating disorder. The systematic devaluation of what is important to women's development influences how women define themselves and how they interact with others (Brown & Jasper, 1993). Kuba and Hanchey (1991) suggest that group treatment is found to be most helpful in integrating a feminist perspective because it allows women to develop their sense of self in relationship to others. These authors describe group therapy for eating disorders as "…the ongoing process of merger and separation which vacillate until stabilization of the self" (p.132). Thus, understanding the oppression of women and utilizing the strength of women in connection through group therapy facilitates the development of self. Summary This study attempts to account for the experiences of the women with eating disorders. By listening and validating the voices of the people who struggle with eating disorders, some of our current understandings of eating disorders are supported and enhanced. Quantitative understandings of eating disorders provide the ability to test, diagnose, and characterize, but give us little information about the actual experience of struggling with an eating disorder. Similarly, quantitative studies can determine that group therapy is useful but provide little information about how or why it is effective. This study began as an attempt to bridge some of the gaps in our understanding of eating disorders and the women who experience them. Limitations of the Study Self-in-relation theory has gained popularity because it portrayed women in ways that celebrated their connections through relationships. However, one should not assume that all women have enjoyed this socialization experience. The roles and relationships of women have shifted over time due to overriding social forces, such as socioeconomic status, race, and political forces that support patriarchy. The intent of this discussion is not to characterize women as having the same experience of self, or to assume all women experience it equally. What constitutes a healthy sense of self in relation for women is diverse. The many constructions of self, represented by the small group of women in this study, illustrate the many ways women consider their health and their relationships. Although this study chose to focus on the experience of women, the omission of men from this study should not be falsely assumed to imply that their experiences are not centered in social connection (Miller, Jordan, Kaplan, Stiver, & Surrey, 1997). Self is formulated through social interaction; however, the meaning and implication of social connection may have diverse meanings for both men and women. Further limitations of this study are in reference to issues of methodology. Small sample size, the whiteness of the sample, lack of follow-up, and lack of application of other data collection methods limit the applicability of the results. This research addressed women's experience in group therapy; however, therapists need to be mindful of the selection and screening process to ensure participants will benefit from group treatment. Further, women of color were not represented in this sample and this unfortunately does not add to our understanding of the experiences of culturally diverse women with eating disorders. Root (1990) takes a strong stand in noting the biases inherent in eating disorder research where diverse populations are not reported and research settings do not include diverse women as participants. It is now understood that eating disorders impact culturally diverse populations and research is just beginning to understand these complexities (Krentz & Arthur, 2001). Future research needs to include the experiences of more than white, middle-class women with eating disorders. Finally, this study was exploratory in nature in that it was one of a limited number of studied that have attempted to uncover the experiences of women participants to determine their perspective on the value of group therapy. Conclusion Despite these limitations we believe that this study provides a basis for further exploring the connections between women's sense of self and eating disorders. The literature on eating disorders is vast and has a long history. Despite all the research, eating disorders continue to be a major issue in women's health. As long as women are socialized to restrict their "selfhood", we can expect difficulties. It is important for practitioners to consider the theoretical perspective that informs their practice. Special consideration should be paid to whose voices have informed each perspective. Acknowledgments The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Nancy Arthur for her contributions throughout the process of writing and editing this manuscript. Works Cited Note: this text conforms to APA format. American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th Ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Anderson, T. (1987). The reflecting team: Dialogue and meta-dialogue in clinical work. Family Process, 26, 415-428. Biever, J.l., & Gardner, G.T. (1995). The use of reflecting teams in social constructionist training. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 14(3), 47-56. Brotman, A.W., Alonso, A., & Herzog, D.B. (1985). Group therapy for bulimia: Clinical experience and practical recommendations. Group: The Journal of Eastern Group Psychotherapy Society, 9(1), 15-23. Brown, C., & Jasper, K. (Eds.). (1993). Consuming passions: Feminist approaches to weight preoccupation and eating disorders. Toronto: Second Story Press. Cantrell, P.J., & Ellis, J.B. (1991). Gender role and risk patterns for eating disorders in men and women. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(1), 53-57. Chodorow, N. (1989). Feminism and psychoanalytic theory. New Haven: Yale University Press. Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3-21. Cross, L.W. (1993). Body and self in feminine development: Implications for eating disorders and self-mutilation. Bulletin of Menninger Clinic, 57(1), 41-68. de Groot, J. (1994). Eating disorders, female psychology, and developmental disturbances. In M.G. Winkler & L.B. Cole (Eds.), Asceticism in contemporary culture. New Haven: Yale University Press. Dorian, B.J., & Garfinkel, P.E. (1999). The contributions of epidemiologic studies to etiology and treatment of the eating disorders. Psychiatric Annals, 29(4), 187-192. Epstein, R. (1990). Eating habits and disorders. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. Frederick, C.M., & Grow, V.M. (1996). A mediational model of autonomy, self-esteem, and eating disordered attitudes and behaviors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 217-228. Friedman, S.S. (1996). Girls in the 90's. Eating Disorders, 4(3), 238-244. Gendron, M., Lemberg, R., Allender, J., & Bohanske, J. (1992). Effectiveness of the intensive process-retreat model in the treatment of bulimia. Group: The Journal of Eastern Group Psychotherapy Society, 16(2), 69-78. Gorman, P., Lockerman, G., & Giffels, P. (1995). Conversations outside the clinic: Video-reflecting teams for in-home therapy and supervision. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 14(4), 1-15. Hall, A. (1985). Group psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa. In D.M Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. New York: The Guilford Press. Henwood, K.L., & Pidgeon, N.F. (1992). Qualitative research and psychological theorizing. British Journal of Psychology, 83, 97-111. Hesse-Biber, S. (1996). Am I thin enough yet? The cult of thinness and the commercialization of identity. New York: Oxford University Press. Kaplan, A.G. (1982). The 'self-in-relation': Implications for depression in women. In Women's growth in connection. New York: The Guilford Press. King, N. (1994). College women: Reflections on recurring themes and a discussion of the treatment process and setting. In B.P. Kinoy (Ed.), Eating disorders: New directions in treatment and recovery. New York: Columbia University Press. Klemchuk, H.P., Hutchison, C.B., & Frank, R.I. (1990). Body dissatisfaction and eating-related problems on college campus: Usefulness of the Eating Disorder Inventory with a nonclinical population. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37(3), 297-305. Krentz, A., & Arthur, N. (2001). Counseling culturally diverse students with eating disorders. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 15(4), 7-21. Kuba, S.A., & Hanchey, S.G. (1991). Reclaiming women's bodies: A feminist perspective on eating disorders. In N. Van Den Bergh (Ed.), Feminist perspectives on addictions. New York: Springer Publishing Company. Laube, J.J. (1990). Why group therapy for bulimia? International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 40(2), 169-187. Lazerson, J. (1992). Feminism and group psychotherapy: An ethical responsibility. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 42(4), 523-546. Mahoney, M.J. (1990). Representations of self in cognitive psychotherapies. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(2), 229-240. McKisack, C., & Waller, G. (1996). Why is attendance variable at groups for women with bulimia nervosa? The role of eating psychopathology and other characteristics. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20(2), 205-209. Miller, J.B., Jordan, J.V., Kaplan, A.G., Stiver, I.P., & Surrey, J.L. (1997). Some misconceptions and reconceptions of a relational approach (pp. 25-49). In J. Jordan (Ed.), Women's growth in diversity. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Phelps, L., & Wilczenski, F. (1993). Eating Disorder Inventory-2: Cognitive-behavioral dimensions with nonclinical adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(4), 508-514. Pipher, M. (1995). Hunger pains: The modern woman's tragic quest for thinness. New York: Ballantine Books. Reed, G., & Sech, E.P. (1985). Bulimia: A conceptual model for group treatment. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 23(5), 16-22. Riess, H., & Rutan, J.S. (1992). Group therapy for eating disorders: A step-wise approach. Group: The Journal of the Eastern Group Psychotherapy Society, 16(2), 79-84. Rolls, B.J., Fedoroff, I.C., & Guthrie, J.F. (1991). Gender differences in eating behavior and body weight regulation. Health Psychology, 10(2), 133-142. Romney, P. (1995). The struggle for connection and individuation in anorexia and bulimia. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 6(4), 45-62. Root, P.P. (1990). Disordered eating in women of color. Sex Roles, 22,(7/8), 525-536. Roth, D.M, & Ross, D.R. (1988). Long-term cognitive-interpersonal group therapy for eating disorders. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 38(4), 491-510. Russell,S. & Arthur, N. (2000). The contribution of a reflecting team to group therapy for women with eating disorders. Guidance & Counselling, 16(1), 24-31. Smith, T.E., Winton, M., & Yoshioka, M. (1992). A qualitative understanding of reflective-teams II: Therapists' perspectives. Contemporary Family Therapy, 14(5), 419-432. Smith, T.E., Yoshioka, M., & Winton, M. (1993). A qualitative understanding of reflecting teams I: A client perspective. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 12(3), 28-43. Steiner-Adair, C. (1986). The body politic: Normal female adolescent development and the development of eating disorders. Journal of American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 14(1), 95-114. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Surrey, J.L. (1991a). Eating patterns as a reflection of women's development. In J. Jordan, A.G. Kaplan, J.B. Miller, I.P. Stiver, & J.L. Surrey (Eds.), Women's growth in connection. New York: The Guilford Press. Surrey, J.L. (1991b). The self-in-relation: A theory of women's development. In J. Jordan, A.G. Kaplan, J.B. Miller, I.P. Stiver, & J.L. Surrey (Eds.), Women's growth in connection. New York: The Guilford Press. Thompson, B.W. (1992). "A way outa no way": Eating problems among African-American, Latina, and white women. Gender & Society, 6(4), 546-561. Turner, B.A. (1981). Some practical aspects of qualitative data analysis: One way of organizing the cognitive processes associated with the generation of grounded theory. Quality and Quantity, 15, 225-247. Wakeling, A. (1996). Epidemiology of anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Research, 62, 3-9. Wuest, J. (1995). Feminist grounded theory: An exploration of the congruency and tensions between two traditions in knowledge discovery. Qualitative Health Research, 5, 123-137. Young, I.M. (1990). Throwing like a girl: A phenomenology of feminine body comportment, mortality and spatiality. In I.M. Young (Ed.), Throwing like a girl and other essays in feminist philosophy and social theory. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. Young, L. (1992). Sexual abuse and the problem of embodiment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 16, 89-100. |