|

Mas(k/t)ectomies: Losing

a Breast (and Hair) in Hannah Wilke’s Body Art |

||

| Julia Skelly |

||

|

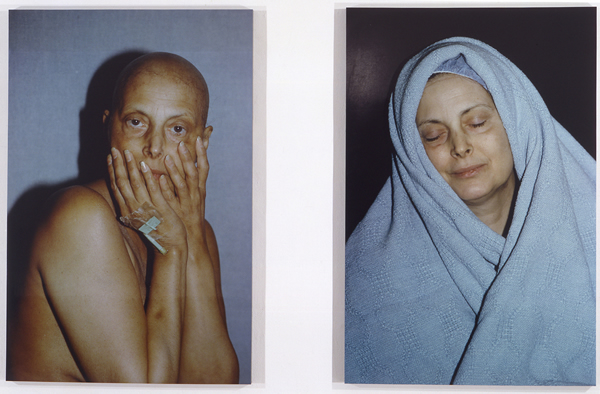

The term ‘mastectomy’ was first used in 1923 to describe the surgical removal of all or part of a breast as a treatment for cancer. The word is an amalgamation of the Greek ectome (which translates as ‘a cutting’) and mastos (woman’s breast). In this article I propose that the objectification of the breast that occurs in Western lived and visual culture causes breasts to function as masks, and they are viewed as such by both the looker and the looked upon. When a woman is looked at with a sexualized gaze, her breasts are often the first part of her that the viewer sees, thus erasing her identity and individuality (the fundamental ambiguity of identity, however, will be central to my discussion, as will the idea that subjectivity is performative). A woman is trained to hide behind her breasts because they are the parts of her most valued in Western society. Breasts, consequently, are comparable to masks in that they veil the complex subject (or subjects) behind them, and, like hair, they are largely accepted as constituent parts of a woman’s normative femininity. Identifying women with or by their hair and breasts is problematic, of course, for those individuals whose bodies do not fit the ideal and for those individuals, such as transgendered persons, who alter their bodies (with hormone treatments or plastic surgery) to fit an alternative paradigm. But the question remains: If breasts and hair are masks of a sort, what happens when they are lost? How is femininity acted out then? I will offer possible answers to these questions by examining examples of body art from feminist artist Hannah Wilke’s (1940-93) late period.[1] Although visual culture studies has opened up space for scholars to study objects of analysis not traditionally examined in the field of art history, which has largely been concerned with painting, sculpture, and sometimes architecture, I locate this study of Hannah Wilke’s photographs within the realm of feminist art history. Feminist art historians such as Linda Nochlin, Griselda Pollock, and Rosemary Betterton have provided a background of scholarship that was never far from my mind as I wrote this article. In 1971 Nochlin asked, “Why have there been no great women artists?” and she went on to argue that the art history canon had, up to that point, been constructed by men to include male artists only. Pollock wrote in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art (1988) that the primary responsibility of feminist intervention into art history is to study women as producers (10). Yet, writing eleven years later, she proposed that scholars move beyond ‘additive feminism’ – the tendency in feminist art history to recuperate historical female artists (Differencing the Canon, xii). In her own work, Pollock began to analyse art using methodologies ranging from Marxism to psychoanalysis. I am concerned here not only with Hannah Wilke as a female producer of art but also with representations of women, namely Wilke and her mother, Selma Butter (1909-82). Taking into consideration the unhappy fact that the majority of women reading this article have likely had some brush with breast cancer, whether direct or indirect, I am more interested in context and meaning(s) than the formal aspects of the artworks. By approaching the images from a vantage point informed by thoughts about illness and its effect on how the body is conceptualized, my analysis will have greater personal resonance for my readers than if I were to limit my discussion to the formal properties of Wilke’s photographs. A veil of silence still shrouds the loss of breasts and hair in art history literature. While the ‘explicit body’ of the feminist artist is no longer a taboo subject due to the work of scholars such as Amelia Jones (1998) and Rebecca Schneider (1997), illness has not been given the scholarly attention it deserves in the context of feminist art. That is not to say, however, that feminist art historians have completely ignored art by feminist artists that addresses breast cancer and the loss of a breast. Amanda Sebestyen has written about the cancer drawings of Catherine Arthur (1992), and Jo Anna Isaak briefly alludes to Jo Spence’s photographs in the final chapter of Feminism and Contemporary Art: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Laughter (1996). Isaak also discusses Hannah Wilke’s Intra-Venus photograph series, even though Wilke died from lymphoma, not breast cancer. Isaak writes that feminist artists who document their battles with critical illness are “triumphant, not because the women win the battle; for the most part they don’t. They are triumphant in their challenge to society’s obsession with masking loss, in their willingness to look steadily at the ‘disappearance that everybody denies’” (221). The loss of a breast is one of those losses that is kept under wraps in Western culture. Doctors recommend reconstructive surgery after they perform mastectomies, and bras with prosthetic breasts are available for purchase by emotionally traumatized women post-surgery. The strict standard of Western beauty – perfection, proportion, clarity, and symmetry (Zeglin Brand 3) – is threatened and transgressed by the woman with one breast. My objective is not merely to contribute to the historiography of feminist artists who have produced artworks inspired by breast cancer (although I do see the importance of such an undertaking); rather, I am concerned with how a woman’s illness, the treatment for that illness, and the resulting loss of hair or a breast from the treatment forces the woman to engage in new performative acts to signify gender identity. I discuss some of Hannah Wilke’s photograph-based works, focusing primarily on Portrait of the Artist with her Mother, Selma Butter (from the So Help Me Hannah series, 1978-81), and the Intra-Venus series (1992-93). I argue that Wilke’s art documents the loss of hair and a breast (her mother’s) and captures women in new performative acts of femininity, using props, poses, and costumes to reconstruct their gender identities. This reconstruction calls attention to the fact that gender identity is just that: a construction dependant on a series of enactments. Judith Butler argues in Gender Trouble that a “performative theory of gender acts” offers a framework through which to read discursive practices that denaturalize the categories of body, sex, gender, and sexuality (xii). I suggest that Wilke’s photographs, the Intra-Venus series in particular, are self-portraits that may be described not only as performance art, in the sense that Wilke is performing stereotypical feminine roles for the viewer, but also as representations of performative acts that disrupt the idea of a coherent or intelligible femininity.[2] I also look at Wilke’s artworks using the critical tools of disability studies because, like scholars who adhere to a performative theory of gender, proponents of disability studies propose that the healthy body, gender, and sexuality are culturally constructed. Finally, I am mindful of Wilke’s persona as a femme fatale, a female artist whose sexual power was regarded as a threat while she was alive, but who, in the end, was killed by her own body. Her final photographs are in essence a masque – her dance with death. Death Becomes Her Hannah Wilke began producing photographs, videos, and performances in the early 1970s, and her whole oeuvre may be described as self-portraiture, as the images, whether still or on video, capture her body in some way.[3] In works such as Super-T-Art (1974) and S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974-82), Wilke appears semi-nude and uses facial expressions, poses, and props to embody various feminine ‘types’ and emotional states. Her titles are significant, as they point to the issues that she is dealing with in her art (her reputation as a ‘tart’ in the art world in Super-T-Art; her Jewish roots and psychic scars in Starification Object Series). Yet, because Wilke used her body to address issues like sexism, racism, and wounds, both physical and psychological, and because that body was deemed beautiful, critics in the 1970s and 1980s persistently ignored the critiques Wilke was activating. They chose instead to be consumed with her body, chastising Wilke as though they were being consumed by her body. Debra Wacks has pointed out that American museums and critics in 1999 still perceived Wilke’s early works as tainted by narcissism, which they deemed inappropriate because women (and women artists) were, and are, condemned for being confident in and about their bodies (1). As has been noted by several feminist art historians before me, Wilke was criticized by both male artists – she had a reputation as a femme fatale in the male-dominated art world because of her rumoured promiscuity with male artists – and by feminists who believed that she used her beautiful body in a way that re-entrenched the objectifying narratives of Western culture. Lucy Lippard set the tone for feminist critics of Wilke’s work when she reprimanded Wilke for confusing “her roles as beautiful woman and artist," as if these ‘roles’ were mutually exclusive (Wacks 2; Lippard 126). Lippard appears to have believed that Wilke’s beauty obscured the issues being raised in her artworks. In other words, Lippard’s argument suggested that only art that did not represent Wilke herself could be considered ‘serious’ art. This reaction against Wilke’s art changed dramatically when her Intra-Venus images – which portray Wilke (almost unrecognizable from the chemotherapy) posing during her treatments for lymphoma – were exhibited posthumously. As Amelia Jones has pointed out, after the exhibition of Intra-Venus in New York in 1994, art critics and other artists began to describe Wilke as transgressive, something she was rarely called when she was alive (185-86). Whereas Wilke’s display of her ‘beautiful,’ healthy, ‘normal’ body was regarded as inappropriate and self-indulgent, depictions of her sick and ‘abnormal’ (heavy, bald, and dying) body were identified as avant-garde and political. Before Wilke became ill with lymphoma in the early 1990s, however, she had witnessed her mother’s struggle with breast cancer. In 1978, Selma Butter makes her first appearance in So Help Me Hannah, a series with a poignant title that recalls the kind of exasperated statement that a mother might make to her daughter during an argument. The statement has a ring of desperation to it, as if the ill mother has reversed normative familial roles by asking her healthy daughter for help that Hannah cannot give. The two women are represented in My Mother (Such a Smart Woman) as healthy and in their ‘natural’ subject positions as mother and daughter. Wilke’s long arms wrap around her mother’s neck in a childlike embrace, and the two women’s features, particularly their identical smiles, signal their relationship to each other. Although both women appear healthy, Butter had already been diagnosed with breast cancer. In other words, both Butter and Wilke are enacting serenity in this image: the former knows she is ill and is facing her own mortality, while the latter must have been dealing with the fear of losing her mother. Yet the viewer would never know that these faces are masks of health and contentment hiding behind them illness and fear. We are duped into a false sense of calm because the two women are such skilled performers. In Portrait of the Artist with her Mother, Selma Butter (Fig. 1), the older woman’s scar is the sign of her absent breast. Debra Wacks notes that the jarring dyptich, which represents Wilke’s youthful beauty juxtaposed against her mother’s mastectomy-scarred body, is “wrought with the emotional and physical trauma of loss” (1). I agree that this work speaks of loss, both of Butter’s breast and the inevitable, approaching loss of Butter herself; however, I contend that Wilke’s representation of her mother in the nude with only one breast and a mastectomy scar contributes to an artistic project that points to gender identity as a series of performative acts. In losing one breast, Butter has also lost the masking function that two breasts activate. In other words, the loss of a breast calls attention to how that breast (when part of a pair) was once viewed: as a primary signifier of sexuality and femininity that masks the complex individual behind the body parts. Yet, not insignificantly, Butter wears a post-chemotherapy wig to hide her baldness, thus achieving the appearance of a normal female body, at least from the neck up. Judith Butler has argued that, “if gender is instituted through acts which are internally discontinuous, then the appearance of substance is precisely that, a constructed identity, a performative accomplishment which the mundane social audience including the actors themselves, come to believe and to perform in the mode of belief” (Gender Trouble, 141). However, because we can see Butter’s mastectomy scar, we do not ‘believe’ this enactment of ‘normal’ femininity. We can see that Butter’s normative femininity is only appearance; therefore, we recognize that gender identity itself is performative – a series of corporeal gestures, which might come in the form of body language, clothing, or even wigs.

Unlike her mother, who turns her face away from the camera, Wilke looks directly at the camera/viewer, establishing fierce eye contact. I find this image of Wilke interesting because it captures the tension between physical ‘perfection’ and ‘imperfection.’ Wilke’s eyebrows are perfectly sculpted, giving her a disdainful expression that is emphasized by the smirk on her lips, which has resulted in deep wrinkles on the left side of her mouth, and her hair is in chaos on the floor around her head. Gravity is pulling on her face so that her left eye is not symmetrical with her right eye. Wilke is presenting to us her own imperfect physicality, which, I believe, negates Amelia Jones’s argument that Wilke’s inclusion of herself in this double-portrait is narcissistic (189).[4] She is not presenting herself as Wilke-the-beauty to her mother’s ‘abnormal’ body, but rather as Wilke-the-actor whose body is captured in this photograph in a flawed state. Finally, Wilke’s garishly made-up face and the toy gun and metal paraphernalia she has placed on her chest indicate that she is engaging in performative acts of gender identity in this photographic performance. She is playing with ‘boys’ toys,’ but she is also ‘playing dress up’ as a ‘big girl.’ Wilke is arming herself with the trappings of Western culture (violence and artifice), and make up, of course, is a mask worn by millions of Western woman each day. Art, Illness, and Feminist Disability Studies The way that the loss of a breast is stigmatized in Western culture allows me to draw connections between feminist art that represents mastectomies and feminist disability studies, which in the last ten to fifteen years has taken up concerns about the constructed nature of the ‘normal’ and ‘whole’ body versus the ‘abnormal’ and ‘fragmented’ body. Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, for instance, writes in Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature that her intention is to “interrogate the conventions of representation and unravel the complexities of identity production within social narratives of bodily differences” (5). The disability studies theorists who I quote here have embraced the notion of performativity, that is, the idea that subjectivity is formed via a series of gestures, corporeal signs, and “other discursive means” (Butler, Gender Trouble, 173). Body parts might be described as corporeal signs, and a female body with one breast is read very differently than a female body with two breasts. As Lennard J. Davis points out, “Breast removal is seen as an impairment of femininity and sexuality, whereas the removal of a foreskin is not seen as a diminution of masculinity” (169). But the loss of a breast is not the only lack that locates a female body as incomplete and therefore ‘abnormal’ within the Western cultural paradigm. According to Lacanian terminology, ‘lack’ refers to a woman’s lack of the phallus, which positions fragmented femininity in relation to masculine wholeness.[5] A woman’s baldness is also regarded as a signifier of lost femininity and fragmentation. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick writes, “Forget the literal-mindedness of mastectomy, chemically induced menopause, etc.: I would warmly encourage anyone interested in the social construction of gender to find some way of spending half a year or so as a totally bald woman” (153). Having suffered from a life-threatening illness, Sedgwick realized that performative acts of gender, sexuality, identity, and the body “can’t be made to line up neatly together” (154). In other words, it was illness that made her realize that the enactment of ‘normal’ subjectivities is a Sisyphean task. Just as Sisyphus had to roll the boulder up the hill every day, so too do many women feel pressure to engage in certain performative acts on a daily basis: to put on make up, fix our hair, smile, and ensure that we appear happy and healthy to the world. Sedgwick’s perspective on illness and the performative gestures that illness forces upon women offers a productive framework through which to view Wilke’s artworks that address her mother’s breast cancer and her own lymphoma. Sedgwick highlights the fact that gender and health are acts that no one will ever be able to perform ‘perfectly’ because ‘perfection’ itself is a construction that is constantly shifting and constantly just out of reach, which explains why performance anxiety is so widespread in Western culture. Wilke activates a similar critique in her art. The healthy Wilke (as artist) acted out normative femininity with confidence, swagger, and tongue-in-cheek. The ill and dying Wilke (as artist) presented a sick, medicalized female body that was missing a primary signifier of femininity, her hair. This latter enactment, even more so than the former (to my mind at least), highlights the fact that ‘femininity’ and ‘femaleness’ are indeed dependant on repeated acts and gestures, and breasts and hair are masks that contribute to the picture of ‘normal’ femininity. The Intra-Venus Series: Letting the Masks Fall In the Intra-Venus series, Wilke references the goddess of beauty and love, but this Venus (that is, her self) is incomplete according to the Western binary of ‘whole’ and ‘fragmented.’ Lennard J. Davis has noted that art historians, when it comes to the female body, tend to see wholeness where there is fragmentation. In critiques of the Venus de Milo, for instance, art historians rarely, if ever, refer to her incompleteness (171). However, unlike the Venus de Milo, it is Wilke’s incompleteness that is most often focused on in art criticism, a trend that I am guilty of perpetuating here by focusing on her baldness as the primary conduit of meaning in these photographs. Wilke’s title is a double entrendre, of course, alluding to what Sedgwick calls “the uncanny appendage of the IV drip” (154), as well as to the figure of Venus, the embodiment of beauty in Western art and myth. The title does not simply point ironically to Wilke as a woman who used to be beautiful but is now (re)presenting herself as an ill, yet still active, artist, it suggests that the viewer is getting an internal glimpse of this Venus: We are meant to think that we are seeing into Wilke even though we see only her body, which, by this time, has been revealed to her audience for two decades. According to Butler, distance from gender and sexuality norms allows us to assess them critically because this distance permits us to suspend or defer our need for them (Undoing Gender, 3). Although Wilke did not choose to distance herself from the norm of ideal female beauty – she underwent chemotherapy for reasons of survival – the results of her cancer treatment forced her into a position from which she had the opportunity to develop critical distance. She was able to realize that she no longer needed normative beauty because it was no longer an option for her. I believe that this critical distance from her own beauty and normative femininity is what allows Wilke to so effectively disrupt the idea of coherent gender identity in the Intra-Venus series. Photographs from Wilke’s Intra-Venus series highlight the performativity of gender by representing the artist, without her ‘mask’ of hair, engaging in performative acts of exaggerated femininity. As already noted, feminist theorists working in disability studies have pointed to the intersecting constructions of gender and the healthy or ‘normal’ body. Margrit Shildrick and Janet Price have observed, “Just as we perform our sexed and gendered identities, and must constantly police the boundaries between sameness and difference, so too the ‘purity’ of the ‘healthy’ body must be actively maintained and protected against its contaminated others – disease, disability, lack of control, material and ontological breakdown” (439). In Intra-Venus Series #1, June 15 and January 30, the photograph on the left makes it impossible to ignore the ‘contaminated other’ of illness and loss of control that Wilke was experiencing over her body at the time. One breast is covered by a nondescript black shirt, while the other is covered almost entirely by thick white tape, which keeps the IV drip stuck to her chest. Wilke wears a white shower cap on her bald head, her face is bloated, and her lips turn down at the corners. In the photograph on the right, Wilke stands totally nude (except for bandages on her hips) with a pot of fake flowers balanced on her head, and her arms are raised in an Odalisque pose. She still has her hair in this photograph, and she offers a tiny smile to the viewer. As with My Mother (Such a Smart Woman), the photograph on the left has a duplicitous edge to it, as the viewer might easily interpret the image as a representation of Wilke between performative acts. I am not arguing that we need to mistrust the feelings of sympathy that this image will inevitably arouse; rather, I wish to highlight the fact that Wilke has deliberately chosen this moment to be turned into art: We are not seeing ‘inside’ her, we are seeing an enactment of gender identity that differs from the gender identity enacted in her earlier self-portraits. In this photograph, however, Wilke is clearly in complicity with the viewer. Her facial expression, pose, and humorous prop tell us that performative acts are taking place; she leaves it to the viewer to decide what they signify. If we read Intra-Venus #1 in the Western fashion from left to right, the manner in which Wilke has juxtaposed the two panels produces a narrative that begins with intense illness and invasion of the body and ends in decreased illness (relatively speaking) and a sort of control over the body achieved through performance and posing. Amelia Jones describes this aspect of Wilke’s artistic performance strategy as the “rhetoric of the pose,” which for Jones signals agency and power. Working from Craig Owens’s discussion of the Lacanian gaze, Jones notes: “Confronted with a pose, the gaze itself is immobilized, brought to a standstill” (154). In Jones’s discussion of the pose, she focuses primarily on Wilke’s early works, such as Super-T-Art and S.O.S. Starification Object Series, but I believe that Wilke’s poses in the Intra-Venus series, while similar to the earlier poses in terms of presenting stereotypical feminine roles and personas, activate a more intensive immobilization of the viewer. As Shildrick and Price have observed, disease in the ill person causes ‘dis-ease’ in the healthy person (or viewer, if we transfer their observation from lived to visual culture) (439). In other words, the objectifying gaze is doubly negated by the enactment of illness in the Intra-Venus photographs. Sedgwick writes, “It’s probably not surprising that gender is so strongly, so multiply valenced in the experience of breast cancer today. Received wisdom has it that being a breast cancer patient, even while it is supposed to pose unique challenges to one’s sense of ‘femininity,’ nonetheless plunges one into an experience of almost archetypal Femaleness” (154). Although Wilke had lymphoma and not breast cancer like her mother, her Intra-Venus series parodies this archetypal femaleness using strategies that Wilke had previously adopted in early works such as S.O.S. Starification Object Series, namely poses, facial expressions, and props. In contrast, the signs of illness in her later photographs estrange the performative acts of femininity in ways that were not possible in her works of the 1970s. In Intra-Venus Series #4, July 26 and February 19 (Fig. 2), we see a bruised and bald Wilke in a stereotypical seductress pose that perhaps alludes to the whore archetype with which she had previously been labeled. On the right, her baldness is hidden under a blanket that transforms her into the Virgin Mary, the dialectical opposite of the fallen woman who is punished for her sexuality with illness and death. Wilke’s eyes are closed, her expression serene, but, as is always the case with her work, the artistic performance is not transparent or simplistic. The blanket, which stands in for the blue robe that is a traditional attribute of the Virgin Mary in Western art, appears, upon closer examination, to be one of those rather thin, rough blankets issued regularly to hospital patients. Wilke as the Virgin Mary, then, is not transcendent, she is the object of the medical gaze, a mortal body that is dying within the walls of a hospital room.

Wilke’s artwork was, and is, typically read as being about sex in some way. In her photographs and performances Wilke usually posed nude or semi-naked, and her poses were often overtly sexual. She also gave her performances titles like Intercourse With… (1977). This explicit sexuality is one of the problems that some feminist art historians have had with Wilke’s body of work. They argue that Wilke’s sexually explicit art could not problematize the objectification of the female body in Western culture because the artist, as subject, was beautiful. This critique stalled when the Intra-Venus photographs were exhibited posthumously in 1994. But before Intra-Venus, Wilke was producing art that made viewers acutely aware of their own sexual peccadilloes. In Wilke’s thirty-five-minute video Gestures (1974), she uses her hands to morph her face into “sexually suggestive orifices” (Jones 168). I believe that Wilke references this video, which Jones reads as making the face into the “penetrable (female) body” (169), through a new lens of illness in Intra-Venus Series #5, May 5 and June 10. The two photographs in Intra-Venus #5 speak to Wilke’s new relationship with her body that is a direct result of her illness. Shildrick and Price write that “in illness and disability, what can be called performative acts – that is the corporeal signs, gestures, claims and desires elicited in embodied subjects – serve no less to produce effects of identity, coherence, control and normativity” (440). Of course, the corporeal signs that mean something in healthy bodies signify something very different in ill bodies. Wilke’s open mouth in #5 is no longer erotic or sexual: the photograph on the left brings to mind a patient waiting for the doctor to place a tongue depressor in her mouth. Although we again have the “penetrable female body,” the invoked penetrating object is no longer the phallus, but rather a medicalized object that is penetrating in order to find out more about the female body’s “contaminated other” – her illness. The photograph on the right is more ambiguous. Wilke’s eyes are closed, and her mouth is open to full capacity, as though she were either yelling or laughing. Isaak discusses the Intra-Venus series in her book Feminism and Contemporary Art: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Laughter, but she never convincingly explains why she has included the images in her analysis of humour in feminist art. It might be argued that the Intra-Venus series is not humorous at all, but tragic and thought-provoking, in the sense that we are witnesses to a woman’s journey towards death, which inevitably reminds of us of our own mortality. I believe it is all of these things. Although the younger Wilke was never an overly earnest artist, the most significant difference between Gestures and Intra-Venus #5 is the way that Wilke’s open mouth in the former signifies eroticism, while in the latter it signifies her laughter at…what? Life? Death? Laughter, though cathartic and liberating, is still part of an artistic performance here, and the roles that Wilke is playing in these photographs – virgin, whore, brave woman laughing in the face of death (because through art she will be immortal?) – are still just that: roles. As always, she is performing for us. Isaak argues that Wilke is the feminist artist who best embodies the destiny of the femme fatale (221), a figure who is punished by death in art, film, and literature. In light of how Wilke was first cast down and then raised up as an icon of feminist art, Isaak’s reading of Wilke’s persona is appropriate in two ways. First, Wilke was (and remains in her imaged self) the threatening woman who knows that she is desirable and flaunts the fact that she knows, and second, her Intra-Venus series speaks to the fact that she is the woman/body that dies. Her body literally killed her. But in the art-world narrative of the fallen-woman-made-good that was constructed after the artist’s death, Wilke experienced a symbolic resurrection because of her death. What resonates most for my own argument is Isaak’s observation, working from Lacan, that “what is so threatening about the femme fatale is not the boundless enjoyment that overwhelms the man, nor that she is so immersed in deception, but the threat that she will go too far, let the masks all fall off, reveal ‘the real’” (223-24, my emphasis). In artworks that shows Wilke bald and her mother with one breast and a mastectomy scar, we are bearing witness to women whose masks of hair and two breasts have been lost. Their subsequent performative acts of gender identity tear the veil off the lie that femininity, which Celia Lury has called the “mask of non-identity” (204), is anything but a series of repeated gestures, costumes, and corporeal signs. In 1994, the year after Hannah Wilke died and the year that the Intra-Venus series was first exhibited in New York, Arlene Croce, a dance critic for The New Yorker, wrote an article entitled “Discussing the Undiscussable,” in which she vehemently critiqued Bill T. Jones for producing what she called ‘victim art.’ Jones, a gay, black, HIV-positive choreographer, was chastised for “working dying people into his act,” which put him “beyond the reach of criticism” (54). Croce wrote, “For me, Jones is undiscussable […] because he has taken sanctuary among the unwell. Victim art defies criticism not only because we feel sorry for the victim but because we are cowed by art” (59). I refer to Croce’s article here because she would no doubt describe Wilke’s Intra-Venus series and Portrait of the Artist with her Mother as ‘victim art,’ and I reject the idea that these works are beyond criticism, or that viewers cannot identify the critique that is being activated simply because the subjects are dying. In a cogent rebuttal of Croce’s text, Marcia B. Siegel argues that, “if Jones is theatricalizing his HIV identity, it’s surely not to portray himself as a victim” (259). I would argue something similar regarding Wilke’s artworks that take up illness as subject matter. By photographing her own performative acts that reconstruct a different femininity in every frame, Wilke’s artworks effectively unmask the performative nature of gender identity. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Erin Hurley for her comments on an early draft of this article and my anonymous readers at for their very helpful suggestions. I am also extremely grateful to Ronald Feldman Fine Arts for their permission to reproduce Hannah Wilke’s photographs, and to Artium for allowing me to reference their Web site in this article. Notes 1 Artium, a gallery of contemporary art in Spain, recently held an exhibition of Hannah Wilke's artworks entitled Exchange Values (5 October 2006 to 14 January 2007). All of the works that I discuss here can be viewed on the gallery's Web site: http://biblioteca.artium.org/dossieres/AR00176/exposicionesenartium.htm. back 2 "'Intelligible' genders are those which in some sense institute and maintain relations of coherence and continuity among sex, gender, sexual practice, and desire" (Butler, Gender Trouble, 17). back 3 Even in her Brushstrokes series from the early nineties, Wilke framed her body, if only synecdochally. For these works she took clumps of her own hair, which had fallen out as a result of chemotherapy, and put them behind glass (See Tierney, 44-49). back 4 Jones contends that Wilke's narcissism was enacted in order to problematize the gendering of artistic subjectivity and the objectification of the female body in Western lived and visual culture (151). With this approach to Wilke's art, Jones is attempting to recuperate the term 'narcissism' by identifying it as part of a radical and empowering performance of the self/body; however, words are not so easily re-appropriated. While I appreciate what Jones is trying to do by re-appropriating the term that has most often been used to describe Wilke's body of work, and re-formulating it as radical narcissism, I believe that by merely reusing the loaded term she risks carrying its negative connotations into her own celebratory reading of the images. back 5 For a discussion of Lacanian theory in the context of feminist art history, see Betterton, 154. back Works Cited Betterton, Rosemary. An Intimate Distance: Women, Artists and The Body. London and New York: Routledge, 1996.Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London and New York: Routledge, 1990. ___. Undoing Gender. London and New York: Routledge, 2004. Croce, Arlene. “Discussing the Undiscussable.” The New Yorker (26 December 1994): 34-59. Davis, Lennard J. “Visualizing the Disabled Body: The Classical Nude and the Fragmented Torso.” In Miriam Fraser and Monica Greco, eds.The Body: A Reader. London and New York: Routledge, 2005. 167-81. Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. Isaak, Jo Anna. Feminism and Contemporary Art: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Laughter. London and New York: Routledge, 1996. Jones, Amelia. Body Art: Performing the Subject. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998. Lippard, Lucy R. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women's Art. New York: Dutton, 1976. Lury, Celia. Cultural Rights: Technology, Legality and Personality. London and New York: Routledge, 1993. Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” In Carolyn Korsmeyer, ed. Aesthetics: The Big Questions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1998. 314-23. Pollock, Griselda. Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art's Histories. London and New York: Routledge, 1999. ___. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art. London and New York: Routledge, 1988. Schneider, Rebecca. The Explicit Body in Performance. London and New York: Routledge, 1997. Sebestyen, Amanda. “The Cancer Drawings of Catherine Arthur.” Feminist Review 41 (Summer 1992): 27-36. Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “Breast Cancer: An Adventure in Applied Deconstruction.” In Janet Price and Margrit Shildrick, eds. Feminist Theory and the Body. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999. 153-56. Shildrick, Margrit, and Janet Price. “Breaking the Boundaries of the Broken Body.” In Janet Price and Margrit Shildrick, eds. Feminist Theory and the Body. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999. 432-44. Siegel, Marcia B. “Virtual Criticism and the Dance of Death.” In Peggy Phelan and Jill Lane, eds. The Ends of Performance. New York: NYU Press, 1998. 247-61. Tierney, Hanne. “Hannah Wilke: The Intra-Venus Photographs.” Performing Arts Journal 18/1 (January 1996): 44-49. Wacks, Debra. “Naked Truths: Hannah Wilke in Copenhagen – Copenhagen, Denmark, and Helsinki City Art Museum, Helsinki, Finland.” Art Journal 58/2 (Summer 1999). [http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0425/is_2_58/ai_55427202]. (19 May 2007) Wendell, Susan. “Feminism, Disability, and Transcendence of the Body.” In Janet Price and Margrit Shildrick, eds. Feminist Theory and the Body. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999. 324-34. Zeglin Brand, Peg. "Beauty Matters." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 57/1 (Winter 1999): 1-10. |