|

The (Mis)translation of Masculine Femininity in Rural Space: (Re)reading 'Queer' Women in Northern Ontario, Canada |

||

| Rachael E. Sullivan |

||

|

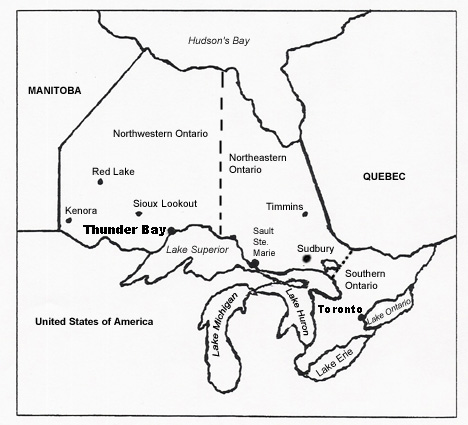

The interplay of gender and sexuality offers a complex relationship among identities, perceptions, and behaviours that are expressed through the body. Characteristics often associated with masculinity and femininity have come to communicate different meanings about sexual identities and desires. The gender cues used to mark the visibility of lesbians and gay men are usually determined by a measure of non-conformity to idealized gender roles—that is feminine women and masculine men, and the stereotypes, behaviours and presentations of self associated with each (Halberstam, In a Queer Time 17). Since the medicalization of gender and sexuality through ‘sexology’, the use of gender non-conformity has served as the basis for identifying ‘abnormal’ sexual and gender identities for both homo and heterosexuals (Foucault 40-49, Fausto-Sterling 14). More recently, alternative gender presentations, roles and beauty norms have created a broader identification of, and greater range in the expression of, sexual (and romantic) desire within the lesbian, bisexual and queer[1] (LBQ) women’s community. Many subgroups exist within this larger community and women may exhibit a variety of appearances that signal their affiliation within these subgroups or the larger queer women’s community as a whole. In either case, the use of specific appearance cues, and the relation of these cues to gender and sexuality, are important in the examination of LBQ women’s visibility and aesthetics, especially within a specific context. In this paper, I explore the reading practices of queer women through the use of gender cues to signal a queer desire and/or sexual identification. Although this paper is focused on the LBQ women who do the (mis)reading, it is likely that these same women also use similar visual cues to communicate their own desires for women. The discussion of these visual practices – via sending and/or receiving – has focused the development of beauty norms that conform to or rebel against gender norms (Hammidi and Kaiser 58). These aesthetic norms develop out of a complex system of normalization (Butler, Undoing Gender 41); the only question is the location/origin of these systems. As will be discussed further, Judith Butler, Judith Halberstam and other queer theorists have worked diligently to trouble the normalization of sex, gender and sexuality. However, as the spatial turn in sociology and women’s studies grows, more attention needs to be paid to the use of spatial metaphors and the material consequences of space and place. Here I have turned to the work of Henri Lefebvre and those who have extended his analysis to provide theoretical concepts that help to link the material effects of space to the production of social processes. Lefebvre provides a useful and compelling analytic for considering the contextual cues used to read the mundane through his conception of the ‘everyday’ and the production of ‘differential space’ (Lefebvre, Everyday Life 9, Urban Revolution 125). In fact, Lefebvre’s conception of the ‘everyday’ adds to Butler’s concerns about the self-conscious construction of the subject and further substantiates the reiterative instability by grounding the discursive production of the subject within a space-specific context. As a result, my aim is to examine how straight ‘burly’ women can be (mis)recognized as queer in the rural space of Northern Ontario, while LBQ women are often (mis)read as straight. Throughout this paper, I argue that the (mis)recognition of straight women by queer women can be explained through a (mis)translation of a ‘butch’ presentation. This is often found in urban spaces, and is then applied to the everyday representation of a masculinized femininity, a highly valued quality within the ‘macho’ landscape of these rural spaces. Moreover, the communication of queer desire through this visual process requires both a sender (citer) and receiver (reader) to signal and understand sexual/romantic attraction. I use the terms (mis)recognition and (mis)translation to indicate a dual process whereby visual cues of masculinity and femininity are used to cite a queer desire/identity. Here, (mis)translation refers to the meaning attached to the specific visual cues associated with ‘queer’ desire and the subsequent interpretation of those cues. This is a risky process since, as Kevin Kumashiro explains, “gay bashers target not only individuals who come out as lesbian/gay/bisexual (LGB), but also individuals who appear to be LGB because they transgress normative gender roles and appearances” (3, emphasis added). As a result, the (mis)recognition of queer bodies as either overly visible or invisible depends on the spatial context of the reading/communication of these cues. To illustrate how this communication process unfolds in rural spaces, I draw on my previous research in Thunder Bay, Ontario, to provide concrete examples. I conclude by identifying some of the problems and possibilities that (mis)reading offers for queer women and explain how the landscape plays an important role for queer women in this specific region. Consequently, this article does not speak directly to the issues faced by transgender men or the specificities of butch-femme culture often associated with lesbian genders. Literature focused on trans issues (see Halberstam, The Brandon Teena 164; Halberstam, In a Queer Time 17; Koening 149-151) and butch/femme culture (see Eves 482; Kennedy and Davis 151-230; Munt 54-94) informs this research, but the phenomena that I describe here do not fit easily within either of these foci. Thus, my intent is to explore the intersection of sexual identity and gender as a bodily practice that is a method of citation and readability. As a result, this paper is about the reading and interpreting of visual cues that signal sexual/romantic desire by women for other women, and the impact of social-spatial context (regionality) on the meaning attributed to these markers, especially the relation changes that occur within rural space. This paper is also limited to qualitative data generated in a research project conducted in 2005, which did not address these concerns, but was focused on the spatial strategies used by LBQ women to navigate their way through Thunder Bay, Ontario. Finding and Losing Lesbians in the Crowd: Sexuality and Rural Spaces It is difficult for a queer community to be visible in a small city or town, especially one that is isolated from Canadian urban centres like Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. There are a number of factors that drive sexual minorities underground and out of public view. In many cases these include intolerance, fear and a lack of services that would meet the needs of a lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer (LGBTQ) community. Since the mid 1990s, there has been a growing amount of research focused on rural places and sexuality (Bell and Valentine 114, Binnie and Valentine 175). In her work on the relocation of lesbians and gay men to more urban areas, Weston comments on the value of urban/rural opposition in stories of migration to San Francisco. She notes, “in most stories of the Great Gay Migration (sic), the rural is not only the space of dead-end lives, oppression and surveillance. It is also a landscape emptied of gay people” (Weston 44). The increased interest in rural places by researchers has helped to challenge the assumption that people with non-normative and non-heterosexual sexual identities could not survive in ‘the country’. While queer folk in rural areas face many challenges, including isolation due to a lack of visibility, I have found, along with other scholars, that these obstacles are met with resourcefulness and resistance. For example, the development of telephone helplines, newsletters and more recently the use of the Internet, aid in the dissemination of information, social activities and sometimes sexual rendezvous (see Bell and Valentine 116). All of these ease the isolation and, even if only momentarily, provide connections to a network of queer folk. Although, the invisibility of gay men and lesbians continues, some rural areas have developed strong informal networks to facilitate the development and maintenance of a queer community based on proximity (Bell and Valentine 119, Valentine, Desperately Seeking Susan 113). Many of these same issues informed my own investigation of the negotiation of rural space by LBQ women, focused on the rural space of Northern Ontario. However, as I reflected on the data generated out of this research, I found that this site also provided an opportunity to think through the differences in how gender presentation is interpreted in rural locations and how the visibility of places are used by LBQ women. Imagined as a harsh land of ice and snow, much of the landscape that defines Northern Ontario is a mixture of boreal forest, mineral-rich bedrock and lakes. In fact, a majority of Thunder Bay’s economic stability is derived from the primary industries of forestry and mining (Dunk 14). Secondary industries like manufacturing, transport and shipping have maintained Thunder Bay’s viability as a ‘gateway’ to the West (Mauro 1). The city serves as a transportation hub, and plays a central role in providing healthcare and education via Lakehead University and Confederation College, for the Northwestern Ontario region. Within this rural and rugged context, I argue that the creation of a lesbian aesthetic is informed by a predominantly white, working-class, masculinity,[2] valued in this part of Ontario, Canada. Here, the region boasts a low population density where, “Northern Ontario comprises almost 89% of the land mass of Ontario but represents only 7.4% of the total population of the province” (Southcott 2). In terms of population diversity, Thunder Bay is a predominantly ‘white’ city, with only 2,640 residents claiming ‘visible minority’ status, out of a total population of 109,000 according to the 2001 Statistics Canada census.[3] However, Thunder Bay has a large Aboriginal population of about 7,250 people reported in the same census statistics. Although the relative homogeneity of the population is characteristic of other rural cities and small towns, Thunder Bay is often thought to hold more employment opportunities, better living conditions and more services compared to smaller towns and reserves (Janovicek 29). This creates a unique combination of cultural and ethnic diversity within the city, but it also results in a great deal of racism that has yet to be resolved (Sullivan, Between Lake, Rocks and Trees). As a result, Northern Ontario is often perceived to be a space dominated by discourses of working class, white masculinity. This perception also works to displace aboriginal people and their communities to the outer edge through a reserve land system, and discourages visible minorities, lesbians, gay men and trans folk from settling in the region.

Although there are many small cities, towns and villages that mark the landscape of Northern Ontario, I chose Thunder Bay as the site of the 2005 research project. This project mapped the perception of and spatial strategies used by LBQ women to navigate through rural space. Within this project, I drew on Lefebvre’s work to capture some of the strategies LBQ women employed as they negotiated their presence within this small city using a socio-spatial analysis. I used my own friendship networks and key LBQ sites,[4] such as the Women’s Centre, Women’s Bookstore and Pride Central discussed below, to advertise the call for participants. In total, twelve self-identified queer women contacted me and participated in face-to-face semi-structured interviews in a location of their choosing. The sample was not meant to be representative, but rather was used to illuminate commonalities and differences in the respondents’ engagement with the city. Within this small sample, the two categories that had the greatest variation within the group were age (five women were in their 20s, three in their 30s and four in the over-40 category), and duration of residence in the city of Thunder Bay. Four women had lived in Thunder Bay for less than a month to five years, four women had lived in the city between six and 15 years, and four others had lived in the region for more than 25 years. The sample was predominantly white, with eleven women identifying themselves as Canadian with European heritage and one woman identifying herself as Ojibwa/Cree. The lack of racialized diversity resulted from the methods used to create the sample, and the over-identification of women who had attended or were attending Lakehead University (this included eight of the twelve women interviewed.) In terms of sexual identification, seven women wanted to be identified as ‘lesbian,’ and some used specific terminology such as ‘country dyke’, ‘bent’, or ‘women-loving’ to personalize their sexuality. Three women used ‘queer’ as their main sexual identification, one woman identified as a ‘dyke’ and one woman used ‘bisexual’ to identify her sexuality. Gender ambiguity was not addressed at the time of the interviews as it was outside of the scope of this research project. While the focus of this paper differs from the focus of the original project, I intend to draw on the data generated to explore how visual cues were paired with spatial contexts to help queer women locate others in the city. To this end, I will consider the theoretical implications for the problem of (mis)translation and how straight women come to be recognized as lesbians in the rural space of Northern Ontario. A Lesbian Look: Citational Practices and the Act of Looking

‘Spotting’ a lesbian, bisexual or queer woman is difficult because beauty norms, aesthetic practices and gender cues are intertwined and unstable. The instability, in many cases, is predicated on the implicitly smooth façade of heteronormativity, which assumes a hierarchal congruency between three factors: sex=female, gender=femininity/woman, and sexuality=hetero desire (Jackson 16). Thus, the use of gender cues, which do not correspond to the ideal or stereotypical gender presentation, help to disrupt the heterosexual matrix that undergirds heteronormativity. This means that there is a direct link between use of self-presentation, aesthetic, and sexual identification through the use of gendered cues. In fact, many scholars have invested time and energy into exploring and understanding how lesbian genders, butch/femme, and trans practices work to reconfigure hetero/homo desire within heteronormative culture (Browne 121-122, Butler, Bodies that Matter 65, Eves 491, Halberstam, In a Queer Time 16-17, Munt 54). Yet few scholars have considered the embodiment of masculinized femininity by straight women (see Devor 89 for an exception), and how this affects queer women’s communities. Additionally, scholars have not focused on the importance of gender cues to communicate lesbian/queer desire outside of butch/femme culture (see Eves 490). Thus, it is with these oversights in mind that I attempt to explain the complex relationship between gender and sexuality as both a form of self-presentation and as a text which LBQ women use to locate themselves in the crowd. Citational Practices: visualizing lesbian, bisexual and queer women’s bodies Theorizing the subtle use and reading of specific cues to identify LBQ women is difficult because, as the works of Judith Butler and others have shown, gender and sexuality exist in an unstable relation. These categories are always already mutually constitutive and dependent upon each other for a congruent reproduction that ‘should’ ultimately result in the communication of heterosexual desire. However, when this congruency breaks down, shifts or ruptures, different possibilities emerge. For instance, Sally Munt has persuasively argued that, “butch is the recognizable public form of lesbianism […] it communicates a singular verity, to dykes and homophobes alike” (54, emphasis in original). Similarly, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick describes her own visibility within a ‘lesbian optic’ as femme. To become visible as femme, she found that “the portal to that place, for women, or for lesbians, or for queers, or just for me, I do not know yet, is marked ‘butch’” (Sedgwick 18). In both of these cases, ‘butchness’ is part of communicating or locating oneself within a ‘lesbian optic’, as Sedgwick describes. Although beyond the scope of this paper, a broader discussion of how femmes are visible to other femmes and how bisexuals locate and communicate their desire would provide a challenge to ‘butch’ as an ideal or archetype, and the power of the symbolic that Munt emphasizes. But for this particular context, the communication of ‘lesbianism’ through a visible form of gender non-conformity, a masculinized presentation, underscores the interrelated relationship between sexuality and gender. Although butch/femme cultures offer other productive possibilities that disrupt the ideal heterosexual relationship, the visibility and reading of a queer identification remains tethered to gendered oppositions. As Butler explains “…the materialization of a given sex will centrally concern the regulation of identificatory practices […] as a critical resource in the struggle to rearticulate the very terms, symbolic legitimacy and intelligibility” (Bodies that Matter 3, emphasis in original). Thus, the intelligibility of LBQ women is regulated through prescribed gender presentations, which depend on a specific referent, be it mainstream hetero ideals, or norms found in smaller specialized communities, within a wider queer community. In either case, the dichotomy between male and female, masculinity and femininity, provides a base or set of relations that can be reconstituted in infinite combinations to produce a gendered presentation that can also signal sexual desire and possibly an identity. These norms are often the unthinking articulations and repetitive actions located in the discursive organization of sex, gender and sexuality. Here we can rely on the ‘regulation of identificatory practices’ to help us determine the sexual desire and/or identity of a given person. However, it is at the level of the mundane, that these everyday norms serve to shape the subject. As Butler has described, this process is a form of citational practice, where “the norm of sex takes hold to the extent that it is ‘cited’ as such a norm, but it also derives its power through the citations that it compels” (Bodies that Matter 13). Butler then asks: “And how it is that we might read the ‘citing’ of the norms of sex as the process of approximating or ‘identifying with’ such norms?” (Bodies that Matter 13). Butler answers her question by considering the regulatory schemas that retain and restrain the criteria through which bodies are produced as intelligible or not. Thus the reading of one’s sexuality is constrained through the ‘everyday’ mundane norms that serve as the referent for the reader. Here, an urban or rural location, or even the subtle differences between cultural beauty standards and aesthetic for women, are part of the ‘everyday’ context which is rooted in location and serves as a focal point for organizing discourses into material effects, which is something Butler does not explicitly consider in her schema. The Act of Looking: locating lesbian, bisexual and queer women in spaces and places To begin with, the literature on sexuality and space, developed over the last three decades, has drawn more attention to specificities of gender, sexuality and space (see for instance, Bouthillette 221-225, Lockard 86, Nash 251, Podmore 233-235, Valentine, Lesbian Geography 3-5). Researchers have found that lesbian neighbourhoods are often situated within a broader counter-culture context, where they are only visible to the ‘enlightened’ viewer (Adler and Brenner 30, Bouthilletter 221, Lockard 88, Rothenberg 165). In some cases, researchers have explored a communication of a community identity through lesbian, bisexual or queer women’s beauty norms and/or a sense of ‘lesbian aesthetic’ (Cogan 77, Eves 492, Hammidi and Kaiser 56). Eves demonstrates that the stylization of the body also becomes a sight/site for the communication of queer desire. As a result, she argues, “fashion, style and beauty practices are key sites in the construction of gendered identities since the body becomes part of a system of signification through these cultural practices” (Eves 492). Although research in this area explores the use of gendered cues to reference lesbian, bisexual and queer identity, the researchers do not consider how reading these ‘significations’ or styles might be misinterpreted within different social/spatial contexts. Indeed, the act of looking and reading requires an understanding of norms and the meanings they signify. The use of gender cues as the medium through which sexuality can be broadcast becomes an important tool for articulating a queer sexuality. As Alison Eves explains, “gender is constructed and enacted through everyday social and cultural practices, through the negotiation of a mixture of shifting and sometimes contradictory cultural arrangements and gendered resources” (492, emphasis added). ‘Everyday’ gender norms provide the discursive material through which different desires can be formed and recast. Although, this appears to contradict the forced reiterative practices of sexual regimes that Butler has defined and defended time and time again, an emphasis on the ‘everyday’ is the key to locating the forcibly produced subject. For Lefebvre, the everyday can be distilled into various rhythms, cycles and repetitions. As he argues, “In order for it [‘the everyday’] to have ever been engaged as a concept, the reality it designated had to have become dominant, […] established and consolidated, [it] remains a sole surviving common sense referent and point of reference” (Lefebvre Everyday Life 9). Additionally, in The Urban Revolution, Lefebvre describes his theory of ‘differential space’ as the layers that organize social space. He remarks,

Here, Lefebvre makes clear that space alone does not provoke changes or differences; rather, for Lefebvre there exists a dialectical interaction between people and the built environment, and therefore what transpires is in relation to urban space. As Sherene Razack explains further, "through these everyday routines the space comes to perform something in the social order, permitting certain actions and prohibiting others. Spatial practices organize social life in specific ways" (9). Here, occupations and activities made available and accessible are often different in rural contexts compared to metropolitan ones. In turn, these activities substantiate and privilege certain subjectivities over others as suggested in the previous discussion of the production of subjects through the mundane. As the mundane 'everyday' shifts from cycle to cycle it is 'the dominant activity' that determines how the space is understood, from which a spatial context emerges as the differences between rural and urban spaces are articulated in the everyday. This provides a more nuanced understanding of how 'butch' might be (mis)translated from urban to rural contexts. Although Butler has developed a useful theoretical construction of sex, gender and sexuality, she does not consider the impact of the spatial as a discursive production that shapes the production of subject. The everyday as conceptualized by Lefebvre is important for considering the locational constraints that shape how identificatory practices are imbued with meaning. Indeed, the shift from urban to rural marks a reorganization of dominant discourses, where a different kind of aesthetic emerges which enables straight women to be (mis)recognized as ‘lesbian’ by outsiders. Residents, on the other hand, have had difficulty finding LBQ women as they tend to assume most women are straight unless they can tell otherwise. Thus, the study of sexuality and gender is complex, especially when taking sexuality as the central concept and wrestling with how it comes to be gendered. However, gender is an integral part of understanding how sexualities are expressed aesthetically. In the next section, I consider the specific ways in which rural space is organized and how this affects gender presentation and the meaning of ‘masculine femininity.’ “Those aren’t Lesbians”: defining the context for a masculine femininity The hinterlands of Northern Ontario provide a specific site to consider the constellation of the landscape, with working class identity and whiteness, which produces a particular definition of masculinity that Thomas Dunk and David Bartol describe as “physical toughness, male solidarity, anti-intellectualism, common sense and an ethnic identity as whites […]” (42). The privileging of these attributes works to reorganize the space of this rural region, while also connecting bodies to the landscape. This results in specific dominant and identifiable characteristics that mark this space as rural and that can be recognized as separate from the bodies and identities available in the metropolitan spaces of Southern Ontario. Consequently, masculinity occupies a privileged place within the discursive organization of the city and region. In fact, the masculinity of space/region has a relational effect on the expression of femininity, which I argue encourages women, at times and within certain boundaries, to ‘be one of the boys’. This may also close down a variety of masculine gendered presentations for men that are targeted as ‘too feminine’, ‘soft’ or ‘weak’. Thus, a masculine femininity is accepted as part of the rural nature of Thunder Bay, yet a feminized masculinity may not be.[5] Although, Moira Gatens urges us to be clear about the use of ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ and female and male, she notes that “the ‘feminine male’ may have experiences that are socially ascribed as ‘feminine’ but […] in a way that must be qualitatively different from female experiences of the feminine” (146). Similarly, in this spatial context, a masculinized femininity is a kind of masculinity that cannot transcend female embodiment. That is, while women are encouraged to be ‘one of the boys’ they cannot actually be ‘a boy’, and the negotiation of this discernable limit provides both possibilities and limits for women living in this region. In fact, I was alerted to the act of (mis)reading in Thunder Bay when I lived in the city, and I was reminded of it in my very first interview. Jane, a white lesbian, who had lived in Thunder Bay for over 25 years, related a specific instance to describe the (in)visibility of queer women in Thunder Bay. She was hosting some people new to the region and recounted their first foray to the grocery store:

The (mis)translation of gendered cues here led to a (mis)recognition of queer sexualities. It frames what I mean by a 'masculinized femininity'. As I have found in my research, women -straight and queer - adopt a more masculine appearance in this rural space due to a combination of landscape, isolation and the privileging of masculine discourses (Sullivan, Between Lake, Rocks and Trees 76-83). Here, Jane captures this moment of (mis)recognition, where outsiders had mistaken women, who were most likely in their early 30s, out at the grocery store in their hiking boots, down coats, short hair or touques rushing home to their husbands and kids oblivious to the fact that they were being 'read as lesbian' by a couple of 'out of towners'. In fact, Jane's recollection illustrates the complexity of citing queerness in a rural place where -due to weather, isolation and an appreciation for outdoor recreation - many women are often found in more rugged everyday apparel, which would not fit as easily in an urban context. Although, this was a common experience shared by many of the women interviewed, this (mis)recognition also works to obscure LBQ women from the heterosexual majority, which complicates the process of establishing connections to the largely invisible queer community for the LBQ women who live there. For example, another informant shared her experience:

As HG explains, identifying LBQ women is difficult based on visual appearance alone. Even though this is not unlike the invisibility of femmes or bisexuals in urban and rural contexts, here the adoption of a 'casual outdoor/sporty chic' softens the dichotomy between butch and femme, providing greater variation for all women. However thinking through this dilemma, HG's reference to what she considers 'a more feminine' expression of queer desire was difficult to recognize, especially within the innocuous space of the mall. Thus, she relies on two strategies to work out who might or might not be queer. First, she clarifies what she means by 'feminine' by referencing women who are 'really butch' to provide an appropriate binary of feminine/masculine visual cues. For HG, in this context, a 'really butch' aesthetic is one that marks the embodiment of excessive masculinity to the extent that passing as a man becomes a possibility, even if momentarily. The effect of this passing is made possible through the privileging of white, working class masculine discourses, which dominate this region. Although this combination of discourses could be found in other areas as well, other racial groups located here or in more urban contexts would draw on different gendered possibilities to communicate their queer desire.[6] Second, HG draws on her recognition of that person as part of the community, especially if she has 'seen them out before'. Here, HG is literally trying to locate them through a queer context, be it friendship networks or queer spaces. Without this prior knowledge, the complexity and instability of reading an 'LBQ aesthetic', even by residents, illustrates some of the difficulty that LBQ women might have in finding each other in a crowd. Returning to Butler's definition of citational practices, where the 'norms of sex' are cited to demonstrate an identification with such norms (Butler, Bodies that Matter 13), we can see that landscape and location are important factors that also shape the definition of these norms. From an outsider's perspective, the (mis)translation of a 'butch-lesbian aesthetic' from urban to rural spaces reveals a hyper-visibility of queer women's bodies. Yet, a 'femme-lesbian aesthetic' does not produce this effect in the same way because it conforms to a stereotypical gender expression, which suggests that women who adhere to conventional, or even stereotypical beauty conventions would remain invisible in both urban and rural contexts. Similarly, bisexual women can remain invisible in both straight and queer communities depending on the gender of their partner. As Clare Hemmings describes "It is not only bisexual desire that gets 'misread' as signaling a particular identity. Femme desire, style, and identity, for example, are often read as 'straight,' even though femme desire has been a founding part of lesbian culture" (157). With such ambivalence attached to sexual desire and expression, various (mis)readings reveal how important Lefebvre's 'differential space' is for the spatial context and the effect on the production of selves. Moreover, since both Jane and HG draw on the everyday and mundane spaces of the grocery store and mall, this illustrates how these spaces do not provide enough cues to help them identify those who might identify as lesbian, bisexual or queer. This (mis)reading of the women within these ‘everyday’ spaces emphasizes the invisibility of queer women’s bodies, making it difficult to connect with a largely invisible community. While this (mis)translation of a masculine femininity isolates and even shields queer women from recognizing themselves, it also provides a mechanism for ‘blending in’ with straight women. This aesthetic approach also provides a degree of anonymity and agency for LBQ women, in terms of style of dress and overall demeanor. By ‘blending in’, LBQ women are not as likely to be harassed or bashed based on appearance alone. This challenges Munt’s assertion that a ‘butch’ aesthetic unquestionably signals a lesbian sexuality, at least within the rural (54). Thus, it is from this context that I continue to ponder: if queer women are able to blend in and get lost in the crowds, how can they stand out and signal their transgressive desire for other women? How can they recognize themselves in the crowd? Lesbian Locations and Landscapes: strategies and possibilities Given the (mis)translation of gender cues, one strategy that some LBQ women have used is to (re)read the landscape and use spatial cues to locate and identify other queer women. In the interviews, I asked informants to list specific spaces where they would expect to encounter women expressing their sexuality more freely, and where they might themselves be more open about their queer desires. The result was a conceptual map that contained many feminist and women-centred spaces that the research informants might visit as they navigated their way through the city. Three institutionalized spaces were mentioned, the Women’s Centre, the Women’s Bookstore and the student resource centres (Pride Central and the Gender Issues Centre) at Lakehead University. As JBB explains:

Here JBB identifies specific locations like women’s bookstores, women’s centres, queer resource centres and gay bars that are frequented and used as a point of entry into the queer community. As a result, these specific places, and the conceptual maps they create, offer insight into a hidden world of queer desire for LBQ women. The frequency with which women can be seen at an event or one of these specific sites, signals the likelihood that they might desire other women as well. Although it is more time-consuming and requires multiple ‘outings’ as JBB suggested, this strategy provides the possibility of finding other queer women without a ‘gay village’ or gay business district found in more urban areas. For this reason, the spatial context is often used in conjunction with citational practices to reveal a complex set of identifications that invoke a queer desire and/or attraction. While these specific sites provide concrete markers for the institutionalization of the queer women’s community in Thunder Bay, other more temporary spaces also work to signal a dissident sexuality. Events such as Take Back the Night, V-Day (Vagina Monologues)[8] and musical concerts can be used as spaces to ‘scout’ for other LBQ women. For example, many informants referred to concerts by a local female ensemble and a recent concert by Canadian indie musician Ember Swift, as places to meet and network with other LBQ women. As an informant named Maddie recalled,

Although this identification

strategy remains unstable and based on untenable

assumptions about the frequency with which

certain women attend these events and spaces,

it does provide some hope or potential in

locating other LBQ women. As Maddie explains,

she did see some straight women she knew from

activist circles, but did not seem to locate

any LBQ women. It is unclear if she was looking

for new LBQ women or women that she would

have known and could have gotten to know better.

Another reason Maddie might have found it

difficult to locate other LBQ women could

be a result of the location of the concert

on the University campus, which might have

affected who attended the concert. Throughout

the interviews many women identified the university

as a queer-friendly space, but access to this

space might be difficult to navigate for women

who were not or never were post-secondary

students (Sullivan, Exploring). As

a result, the women that Maddie was looking

for that night might not have wanted to go

to the concert at the university, but would

have gone if it was held at another venue.

Similarly, the timing of the concert could

have altered who was able to attend. If it

was a weeknight, many working women or those

with family responsibilities might have preferred

to stay home, rather than go out. In any case,

the concert would have attracted a predominantly

student audience, where age and temporary

resident status would lead to the use of different

visual cues to signal a non-heterosexual identity.

Indeed, Maddie’s difficulty in finding

other LBQ women, despite following the standard

assumptions about what events lesbian, bisexual

or queer women might attend, highlights issues

of visibility within this specific region.

Other women have used their interest in sports and the outdoors to locate other lesbian, bisexual and queer women in Thunder Bay and the surrounding region. This often takes the form of women’s sports, specifically hockey, softball and rugby. One informant described her connection to the queer women’s community:

By joining the rugby team, Pearl used a specific strategy to find other women 'who were into other women', which confirmed her own desire for women. Her connection to a group of women, within the rugby team, who identified as lesbian, bisexual, or queer, provided a specific site to locate other LGB women and also emphasises the invisibility and difficulty of finding queer women in Thunder Bay. In addition to organized sports, outdoor recreation groups have also helped to bring LBQ women together in specific venues that provide another spatial context within which queer women can use the landscape to cite a queer sexuality and desire. Other participants mentioned getting away from the city momentarily eases the surveillance of the city and offers a new terrain to ‘be themselves’ and with their LBQ lovers and friends (see Sullivan, Between Lakes, Rocks and Trees 81-83). Using outdoor spaces allows for LBQ women to negotiate how they engage with the landscape and how they would read themselves and others within a particular context. This type of strategy would fit within Gill Valentine’s conception of time-space negotiation, where she found that the lesbians she interviewed would use specific avoidance strategies to alter everyday interactions with other people (Negotiating Space-Time 241-245). As a result, the LBQ women of Thunder Bay have used specific spaces, including sports fields, arenas, and the outdoors to negotiate their sexual desire for other women. Accordingly, the informants use these sites as part of the citational practices which include reading places, events or gatherings along side or in addition to the reading of a queer aesthetic and/or body. The incorporation of the landscape into the citational practices of queer women living in Thunder Bay illustrates how the organization of space through the ‘everyday’, as Lefebvre suggests, allows specific sites to become a “common sense referent and point of reference” (Everyday Life 9). Queer women who reside in Thunder Bay have adapted a spatial acuity and incorporated this into their citational and reading practices. In the everyday spaces of the mall and grocery store, mentioned by HG and Jane respectively, the visibility of LBQ women relies only on self-presentation or aesthetic. These spaces are mundane and cannot provide any other information based on visual cues alone. However, other spaces provide more insight, like the Women’s Centre, Women’s Bookstore and university campus, and the spaces created by group activities (sports, outdoor recreation and arts), and events that are affirming to women in general (concerts, festivals and activist events). These provide another layer of information that LBQ women can use to ‘cite’ their queer desire and help others to read and identify it. Thus, being able to ‘read’ the landscape is an important strategy for LBQ women in rural spaces. While these more ‘public’ venues provide a partial view of the queer women’s community, they also provide an opportunity to connect with different women and those who are new to the community/city. More ‘private’ spaces, like house parties and potlucks, allow closeted queer women to socialize without fear of being ‘outed’ (Sullivan, Between Lake, Rocks and Trees 80). In either case, (re)reading the landscape for queerness offers many LBQ women an innovative strategy that works to locate other LBQ women without necessarily having to put themselves at greater risk in the homophobic and heteronormative context of the rural space of Northern Ontario, and specifically Thunder Bay. As a result, this strategy does allow queer women to utilize their ability to ‘blend in,’ although it can still be difficult to meet other queer women and find friends and lovers in a small town. Conclusion Throughout this article, I have outlined the reading practices used by LBQ women to differentiate between heterosexual and LBQ women, and the spatial strategies that accompany this reading process. By employing a socio-spatial approach, I have found that spatial context matters when identifying and locating LBQ women within the rural space of Northern Ontario. In fact, this research reveals how LBQ women use spatial cues and strategies to communicate their sexual identity and desire within a largely invisible community. It also contributes to a wider body of scholarship that acknowledges the resourcefulness of LBQ women in rural places to create and maintain queer-identified communities, without the services typically found in urban centres (see Bell and Valentine 114). As a result, LBQ women use two specific strategies to signal their transgressive desire. First, they frequent sites that are associated with the queer women’s community, like the women’s centre or women’s bookstore, and/or they attend events that would be associated with queer-friendly or women-centred associations and groups. Second, when in mundane or ‘everyday’ places, LBQ women rely on past instances where they might have ‘seen someone out before’. Again the location and context are important and provide additional information about women who might identify as lesbian, bisexual or queer, which cannot be ascertained from appearance alone. Moreover, my examination of a ‘masculine femininity’ within a rural context demonstrates the necessity of conceptualizing gender and sexuality as relational social categories that are not fixed or stable within a binary configuration. As more research is published on female masculinities (see Browne 122; Halberstam, In a Queer Time 17; Munt 58), the distinction between gender presentations and sexualities becomes more varied and nuanced. However, the impact of regional differences, produced through the discursive configuration of power and dominance, further complicates how gender and sexuality are understood and portrayed. In fact, ‘masculine femininity’ portrayed by straight women provides another reading of gender practices, which fit within the male-dominated space of Northern Ontario. Not only does this reading reformulate how straight women might be (mis)recognized as lesbians, but it also signals a shift of non-normative gendered aesthetics from the marginal to the mainstream. Yet, it is unclear if the adaption of a ‘masculine femininity’ by straight women will challenge the future of sexualities, or maintain the heteronormative mainstream within this region. To explore this further, more research needs to be undertaken that will address these issues in specific ways. First, an exploration of the phenomenon I have termed ‘masculine femininity’ needs to be taken up specifically in a rural context. This means that heterosexual women need to be asked about their ideas and approaches to beauty and aesthetic forms. How might they understand their own ideas around self-presentation and gender norms within the rural ‘everyday’? By placing the focus on heterosexual women and their experiences of being (mis)recognized as queer, another dimension will be revealed. Second, LBQ women, within the rural context, need to be asked more specifically about their understanding of self-presentation and aesthetic possibilities. I see this as a missed opportunity within my own research, but one that should be followed up. A third area of research would focus on the citational practices of bisexuals (both male and female) and their relationship to gendered practices within either an urban or rural context. This would provide another facet to understand the relationship between sexuality and gender, and might open up new possibilities between desire, attraction, and bodies. Lastly, within all of these research directions, special attention needs to be paid to the intersection of gender, race, ethnicity, culture and class to more fully understand the interplay of gender and sexuality. The impact and importance of these differences will certainly shape and re-shape how we come to understand gender and sexuality within a spatial context. In this reflection, Northern Ontario provides one opportunity to study gender and sexuality, but more attention could be focused on the challenges and possibilities faced by lesbian, bisexual, queer, transgender, or two-spirit women within the Aboriginal communities, found in this and other regions. Overall, this paper adds to a growing field of both sociological and feminist examinations of gender and sexuality, which consider the importance of space, place, and location. Acknowledgements Thanks to Bonar Buffam, Jacqueline Schoemaker Holmes, Shelly Ketchell, Brandy Wiebe and Marie Vander Kloet for helpful feedback and encouragement on earlier drafts of this paper. I would also like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of for their invaluable comments and suggestions. Lastly, I am grateful for the funding provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council which made this research possible. Notes 1 I use the term 'queer' as a category of identification that captures the fluidity, variations and inconsistencies found in non-heterosexual identities and desires. It is especially useful for interrupting how labels might be shaped through either secrecy or defiance to fit the unique social landscape of rural spaces as found in the work of Bell & Valentine (118), and Kramer (200). back 2 Here the intersections of whiteness and working class discourses produce a particular rugged, macho masculinity. A specific discussion of whiteness in Thunder Bay, Ontario, can be found in Dunk (33). back 3 This information can be found in the 2001 community profiles at this link. back 4 For a more specific discussion of these sites in Thunder Bay, Ontario, see Sullivan (Exploring). back 5 I have defined 'maculinized femininity' as separate from 'female masculinities' because these women are unlikely to be mistaken for men, rather it is their sexuality that is (mis)read. back 6 For example, Patricia Hill Collins provides an excellent overview of how gendered and racialized discourses interact and transforms the material possibilities for both heterosexual and LGBTQ black Americans in the urban context (88). back 7 Gaydar is a colloquial term used to describe an innate talent for spotting other gay/queer people based on a set of codes and behaviours. Shelp, S. G. "Gaydar: Visual detection of sexual orientation among gay and straight men." Journal of Homosexuality 44/1 (2002): 1-14. back 8 'V-Day' is an annual charity production of Eve Ensler's Vagina Monologues with the money raised going to local women's organizations. back Works Cited Adler, S. & Brenner, J. “Gender and Space: Lesbians and Gay Men in the City.” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 16/1 (1993): 24-34. Bell, David & Valentine, Gill. “Queer Country: Rural Lesbian and Gay Lives.” Journal of Rural Studies 11/2 (1995): 113-122. Binnie, J. & Valentine, Gill. “Geographies of Sexuality - A Review of Progress.” Progress in Human Geography 23/2 (1999): 175-187. Browne, Kath “‘A Right Geezer-Bird (Man-Woman)’: The Sites and Sights of ‘Female’ Embodiment.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographers 5/2 (2006): 121-143. Bouthillette, Anne-Marie. “Queer and Gendered Housing: A Tale of Two Neighbourhoods in Vancouver.” In B. Ingram, A. Bouthillette & Y. Retter, eds. Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. Seattle, Wash.: Bay Press, 1997. 213-232. Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter. New York: Routledge, 1993. ___. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge, 2004. Cogan, Jeanine. “Lesbians Walk the Tightrope of Beauty: Thin Is In but Femme Is Out.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 3/4 (1999): 77-89. Devor, Holly. Gender Blending: Confronting the Limits of Duality. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989. Dunk, Thomas. It's a Working Man's Town: Male Working-Class Culture, 2nd ed. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003. Dunk, Thomas & Bartol, David. “The Logic and Limitations of Male Working-Class Culture in A Resource Hinterland.” In Bettina van Hoven and Kathrin Hörschelmann, eds. Spaces of Masculinities. New York: Routledge, 2005. 31- 44. Eves, Alison. “Queer Theory, Butch/Femme Identities and Lesbian Space.” Sexualities 7/4 (2004): 480-496. Fausto-Sterling, Anne. Sexing the Body. New York: Basic Books, 2000. Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, 1st American ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978. Gatens, Moira. “A Critique of the Sex/Gender Distinction.” In Sneja Gunew, ed. A Reader in Feminist Knowledge. New York: Routledge, (1991), 139-160. Halberstam, Judith. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: New York University Press, 2005. Halberstam, Judith. “The Brandon Teena Archive.” In Robert J. Corber & Stephen Valocchi, eds. Queer Studies: An Interdisciplinary Reader. New York: Blackwell Publishing, (2003), 159-169. Hammidi, T. & Kaiser, S. “Doing Beauty: Negotiating Lesbian Looks in Everyday Life.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 3/4 (1999): 55-63. Hemmings, Clare. “From Landmarks to Spaces: Mapping the Territory of Bisexual Genealogy.” In B. Ingram, A. Bouthillette & Y. Retter, eds. Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. Seattle, Wash.: Bay Press, 1997. 147-162. Hill Collins, Patricia. Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender and the New Racism. New York: Routledge, 2005. Jackson, Stevi. “Chapter 1: Sexuality, heterosexuality and gender hierarchy: Getting our priorities straight.” In C. Ingraham, ed. Thinking Straight: The Power, the Promise, and the Paradox of Heterosexuality. New York: Routledge, 2005. 15-38. Janovicek, Nancy. No Place To Go: Local Histories of the Battered Women’s Shelter Movement. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007. Kennedy, E. L., & Davis, M. D. Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community. New York: Routledge, 1993. Koening, S. “Walk like a Man: Enactments and embodiments of masculinity and the potential for multiple genders.” Journal of Homosexuality 3/4 (2002): 145-159. Kramer, J. L. “Bachelor Farmers and Spinsters: Gay and Lesbian Identities and Communities in Rural North Dakota.” In David Bell & Gill Valentine, eds. Mapping Desire. New York: Routledge, 1995. 200-213. Kumashiro, Kevin. “Queer Students of Color and Antiracist, Anitheterosexist Education: Paradoxes of Identity and Activism” In Kevin Kumashiro, ed. Troubling Intersections of Race and Sexuality. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc, 2001. 1-26. Lefebvre, Henri. “Everyday Life.”

Yale French Studies 73 (1987):

7-11. Lockard, D. “The Lesbian Community: An Anthropological Approach.” Anthropology and Homosexual Behavior 11/3-4 (1986): 83-97. Mauro, J. M. Thunder Bay, a history: The golden gateway of the great northwest. Thunder Bay, Ontario: Lehto Printers, 1981. Munt, Sally. Heroic Desire: Lesbian Identity and Cultural Space. London: Cassell, 1998. Nash, Catherine. “Siting Lesbians: Urban Spaces and Sexuality.” In Terri Goldie, ed. In a queer country: Gay and lesbian studies in the Canadian context. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp, 2001. 235-256. Podmore, J. A. “Lesbians in the Crowd: Gender, Sexuality and Visibility Along Montréal’s Boul. St-Laurent.” Gender, Place and Culture, 8/4 (2001): 333-355. Razack, Sherene. “Introduction: When Place Becomes Race.” In Sherene Razack, ed. Race, Space and the Law: Unmapping a White Settler Society. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2002. 1-20. Rothenberg, Tamara. “And She Told Two Friends': Lesbians Creating Urban Social Space.” In David Bell & Gill Valentine, eds. Mapping Desire. New York: Routledge, 1995. 165-181. Sedgwick-Kosofsky, Eve. “‘Gosh, Boy George, You Must Be Awfully Secure in Your Masculinity’”. In Maurice Berger, Brian Wallis, and Simon Watson, eds. Constructing Masculinity. New York: Routledge, 1995. 11-20. Southcott, Chris. “Population Change in Northern Ontario: 1996 to 2001 (2001 Census Research Paper Series: Report #1)” Prepared for the Training Boards of Northern Ontario. (April 2002.) [http://www.trainingboard.com/FeedStream/Content/report1-eng.pdf] (October 15, 2008). Statistics Canada. Community Profiles:

Thunder Bay CMA. Statistics Canada

Catalogue no. 93F0053XIE. (Released June

27, 2002. Last modified: 2005-11-30) [http://www12.statcan.ca/english/Profil01/CP01/Index.cfm?Lang=E] Sullivan, Rachael, E. “Exploring

an Institutional Base: Locating a Queer

Women’s Sullivan, Rachael, E. Between Lake, Rocks, and Trees: Exploring how lesbian, bisexual, and queer women access rural space in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Unpublished MA thesis. Toronto: University of Toronto, 2005. Valentine, G. “Desperately Seeking Susan: A Geography of Lesbian Friendships.” Area 25/2, (1993): 109-116. ___. “Negotiating and managing multiple sexual identities: Lesbian time-space strategies.” Transactions of the Institution of British Geographers 18, (1993): 237-248. ___. “Introduction.” In G. Valentine, ed. From nowhere to everywhere: Lesbian geographies. New York: Harrington Press, 2001. pp. 1-10. Weston, K. Long slow burn: Sexuality and social science. New York: Routledge, 1998. |